Tips for identifying decorative stones -- Introduction

In this section

Decorative stones can have a wide variety of colours and patterns, depending on their compositions and how they formed. When it comes to identifying them, it helps to know a bit of geology. This short guide introduces rocks, minerals and fossils, and points out some things to look out for when identifying a polished stone. It uses examples from Corsi's collection to help explain a number of useful geological terms.

You can search the database by entering some terms that describe the geological features, colours and patterns that you see. Compare your stone with the resulting gallery of images to see if any match. You can then read about each stone sample to find out what Corsi wrote about it and what we know about it today.

Remember … It is useful to have a torch when identifying stone in a dark building. Take a hand lens or magnifying glass as well to see smaller details. If a piece of stone is small enough, it can be examined under a binocular microscope.

If you are photographing a decorative stone to help identify it, take a general view and then use the macro setting to take really sharp close-up pictures, adding a small coin or measure to indicate scale. Avoid using flash if you can, as it will reflect off the polished surface.

Time and place

People have been polishing stone for its beauty and usefulness since prehistoric times. The ancient Romans sourced vast quantities of the choicest varieties from all around the Empire to decorate the buildings of Rome. Many Italian quarries opened to supply marble for the churches and palaces of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods, while in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a renewed interest in the boldly marked, colourful stones used by the ancient Romans. Concrete and glass may have dominated 1960s architecture, but by the end of the 20th century, stone was again in demand, particularly the neutral coloured limestones and granites.

The stone trade is now global, so blocks quarried in one country, may be shipped to another for cutting and polishing, and yet another for final use. Much of the polished stone we see today comes from the Middle East, Asia and South America. When identifying a decorative stone, it is important to think about where and when it was used. A stone's context can offer some useful clues to its identity.

A few stones have been quarried fairly continuously for many hundreds or even thousands of years, but most have been extracted only at certain times in human history. So, an ancient artefact is unlikely to be made of a stone that has only been quarried in more modern times.

On the other hand, a stone that was quarried thousands of years ago does not always indicate an equally old artefact. People have been recycling stone since ancient times. For example, round disks of marble sawn from ancient Roman pillars were often inlaid in the walls of later buildings.

There have always been trends and fashions in the use of stone. When a stone is found in an archaeological excavation, historic building or in antique furniture, the age of the building or artefact can give useful clues to the identity of the stone.

A bit of local knowledge can also be useful. Some stones were only ever used near the place they were quarried, while others have been transported all around the world. Even these may have been used in the vicinity of the quarries for centuries before they were employed in the buildings of other towns and cities. A geological survey, museum geologist, or university geology department will often have specialist knowledge of the stones quarried in their area.

A bit about names

All sorts of names are given to decorative stones. There are Latin names used in antiquity, traditional names used by the Roman scalpellini of Corsi's time, the classifications and trade names of the modern stone industry, and finally, the scientific terms used by geologists.

The Latin names for decorative stones used by ancient authors and recorded by Corsi in his catalogo ragionato, are particularly of interest to archaeologists today.

Most of the contemporary names for stones used by Faustino Corsi are the ones that were used by the scalpellini, the stone cutters of Rome, for example rosso Verona and serpentina ranocchia. They often refer to the colour of the stone and the place it was quarried. The scalpellini appended antico to indicate an ancient stone from the ruins of Rome.

In the stone trade today, any carbonate rock, whether limestone or marble, is classified as a 'marble' if it takes a good polish. Similarly, various different rocks composed of silicate minerals are classified as 'granites'. Other classes of stone used by the trade include 'limestone' (if a carbonate rock doesn't pol/ish well), 'travertine', 'sandstone' and 'slate'.

Many trade names are used for marketing decorative stones. These sometimes indicate the place of quarrying for example Chiampo fiorito comes from the area of Chiampo in Italy. A few bear a very similar name to a better known stone, for example Turkish Rosso lepanto, and the better known Italian Rosso Levanto. Usually), but usually they are fanciful names aimed to appeal to customers, such as Blue pearl, or Sea green. Trade names need to be used with some caution.

In geological nomenclature, decorative stones are much more diverse. For example, Corsi's collection includes:

igneous rocks such as granites, gabbros, diorites, andesites and phonolites;

sedimentary rocks such as limestones, travertines, sandstones, breccias and conglomerates;

metamorphic rocks, including marbles, quartzites, serpentinites, and gneisses;

minerals such as rhodonite, fluorite, and gypsum; varieties of quartz such as rock crystal, amethyst and jasper; and the feldspars amazonite, adularia and labradorite.

Quick Glossary

- actinolite

- agate

- alabaster of archaeologists

- alabaster of geologists

- algae

- alkali feldspars

- amethyst

- ammonites

- amphiboles

- amygdales

- andesite

- anhedral

- aragonite

- belemnites

- bioclasts

- biotite

- bioturbation

- bivalves

- brachiopods

- breccia

- breccias

- bryozoa

- calcarenite

- calcareous

- calcilutite

- calcite

- cavities

- cement

- chalcedony

- chlorites

- clasts

- coarse-grained

- colour

- conglomerate

- conglomerates

- coprolites

- corals

- crinoids

- dacite

- dendrites

- diabase

- diagenesis

- diorite

- dolerite

- dolomite

- dolostone

- echinoids

- epidote

- euhedral

- extrusive igneous rocks

- feldspars

- feldspathoids

- fine-grained

- fluorite

- folded

- foliated

- foraminifera (forams)

- fossils

- fossils

- fractures

- gabbro

- garnets

- gastropods

- gneiss

- goethite

- granite

- granodiorite

- gypsum

- hardness

- hematite

- hornblende

- igneous rocks

- ignimbrite

- intrusive igneous rocks

- jasper

- lapilli

- lazurite

- leucite

- limestone

- lumachella

- magma

- marble

- matrix

- medium-grained

- megacrysts

- metaconglomerate

- metagabbro

- metamorphic rocks

- micas

- micrite

- minerals

- monochrome

- monomict

- muscovite

- nepheline

- obsidian

- obsidian

- olivines

- onyx marble

- ooliths

- orbicular

- orthoceras

- ossicles

- paesina effect

- pegmatite

- phenocrysts

- piemontite

- plagioclase feldspars

- polychrome

- polymict

- poorly-sorted

- porphyroblasts

- porphyry

- potash feldspars

- pyroclastic rocks

- pyroxenes

- quartz

- rock crystal

- rocks

- sandstone

- sedimentary rocks

- serpentines

- serpentinite

- sheared

- siliceous

- sodalite

- spar

- sponges

- stromatactis

- subhedral

- sutured

- tectonites

- tephra

- tephrite

- trace fossils

- trace fossils

- travertine

- tuff

- veins

- vesicles

- well-sorted

Minerals, rocks and fossils – introducing some geological terms

Minerals are the basic building blocks of the inorganic natural world. Rocks are made up of minerals.

Each mineral has a particular chemical composition, and nearly all are crystalline because the atoms are arranged in a regular geometric pattern. Some rocks are made of just one mineral but most are composed of a mixture. It is minerals that give rocks their colours and patterns, and many of their physical properties. Even fossils, the lithified remains of ancient plants and animals, are made up of minerals.

You can read about some of the minerals that make up decorative rocks.

Rocks are classed as igneous, sedimentary or metamorphic, depending on how they form.

Igneous rocks crystallise out as molten rock, called magma, cools. When rocks are eroded by the effects of water, wind and ice, the fragments accumulate and are cemented together to form sedimentary rocks. Sedimentary rocks also include muds precipitated at the bottom of hot springs and deep oceans, and salt deposits formed by evaporation of seas. When rocks are altered by the action of high temperatures and/or pressures, they are said to be metamorphosed. Metamorphic rocks form, for example, around igneous intrusions and where continental plates are pushing together to throw up mountain chains. You can also find out more about the different kinds of rock used for decorative stone here.

Decorative rocks date from different times in the Earth's history. The names and timescales for the different periods of geological time are shown in the International Commission on Stratigraphy's International Stratigraphic Chart.

Fossils are the preserved remains of ancient plants and animals, while trace fossils are the tracks, burrows and other evidence of past life preserved in rocks.

Mollusc shells, corals and sponges are among the many fossils that feature in many decorative stones.

Identifying stone - some things to look for

Answer the questions to find out more about your decorative stone.

Colour

Is the stone the same colour all over (monochrome), or is it a mixture of different colours (polychrome)?

The purest marbles, limestones, travertines and alabasters are white, but small amounts of mineral impurities can tint them beautiful colours.

Hematite and goethite are responsible for most pinks, purples, reds, oranges, and yellows. Iron-bearing silicate minerals including chlorite, actinolite and serpentine give a green colour. Graphite makes a marble grey or black, while bitumen can turn a limestone brown or black.

For some stones, the colour or palette of colours is a distinctive feature that helps with identification.

Remember… when monochrome marbles and limestones lack other distinctive features, they can be impossible to distinguish by eye. A thin section of the stone under a petrological microscope reveals the size and shapes of the grains and may give other clues to its geological history. Other procedures analyse, for example, what trace elements are present, or the isotopic composition of the stone. The results of these tests, when compared with that for well-provenanced reference specimens, can indicate where a stone is from.

You may be able to see individual grains of coloured minerals in metamorphic rocks and igneous rocks such as gneisses and granites.

Remember… polishing helps to bring out the colour. An unpolished stone will have a duller colour, and black marbles look grey until they are polished.

Crystals and grains

How big are the crystals or grains making up the stone? Are they all the same size? What shape are they?

If the grains are big enough to see with the naked eye, it is a coarse-grained rock. You will need a hand-lens to see the individual grains in a medium-grained rock. If the grains are too small to see, even with a hand lens, it is a fine-grained rock. Minerals in a fine-grained rock can be identifiedby examining a very thin slice under a petrological microscope. A natural glass such as obsidian, a rapidly cooled volcanic rock, shows no grain structure at all.

Well formed crystals with straight sides are said to be euhedral. If they are not well formed and only just show the crystal shape, they are subhedral. If they are irregular grains and do not show the crystal shape at all, they are anhedral.

Are the crystals or grains all the same mineral, or are they a mixture? Are they randomly mixed together? Does your rock have larger crystals in a fine-grained groundmass?

If so, it is probably an igneous rock called a porphyry, and the big crystals are called phenocrysts. Metamorphic rocks can also have this texture, in which case the large crystals are called porphyroblasts. The term megacrysts applies to large crystals in a fine-grained groundmass, whether they are phenocrysts or porphyroblasts.

Euhedral phenocrysts in a porphyry.

Anhedral porphyroblasts in a metamorphic rock

Looking at each mineral in the stone, can you identify it? Look at its colour and lustre, test its hardness and look at the shapes of any crystals.

Is your stone a soft calcareous rock such as limestone, marble or travertine, or a hard siliceous rock such as a granite or gneiss?

While the colour of a mineral may depend on any impurities present, its lustre, the way it reflects light, may be more distinctive. Crystals of hematite and pyrite, for example, have a metallic lustre, while the thin flakes of muscovite and biotite mica are particularly shiny and reflective.

Each mineral has a particular hardness. Gypsum (calcium sulphate) is very soft and can be scratched with a fingernail. Calcite and dolomite are harder but easily scratched with a pen-knife. The feldspars are about the same hardness as a penknife blade. Quartz is too hard to be scratched with a penknife blade. Remember, always test hardness at an inconspicuous place on a sample.

You can also test for calcite by placing a small drip of dilute acid (spirit vinegar or lemon juice may just work) and seeing if it fizzes, or leaves a mark on the stone when it is wiped off, but BEWARE, a positive result will damage a polished surface!

The geometric shapes of well-formed crystals among the grains in a rock can give a big clue to the identity of the mineral.

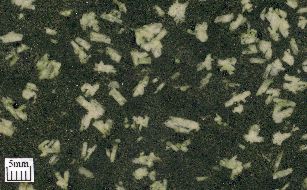

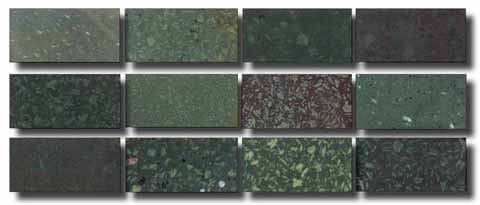

Remember… polished stone is a natural material that can show quite a lot of variation in colour and pattern, even among samples from the same quarry. However, many decorative stones have particular characteristics that mean they can be identified quite easily.

Examples of serpentino verde antico in Corsi's collection showing how it varies in appearance.

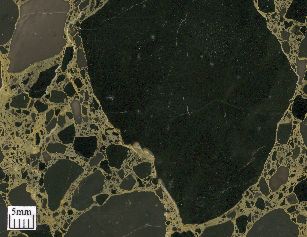

Rocks within rocks

Is the stone composed of pieces or pebbles of rock cemented together? Are the clasts (the pieces or pebbles of rock) rounded or angular?

Rocks with rounded clasts are called conglomerates. The clasts are pebbles worn smooth by the action of water or wind before being cemented together to form a new rock.

A conglomerate

Rocks with angular clasts are called breccias. They are formed where a rock has been broken up, for example by an earthquake or flood, and quickly cemented together again.

A breccia

What kind of rocks are the clasts made of?

If they are too hard to scratch with a penknife, they are most probably composed of quartz or hard silicate minerals. If they are softer and have fossils in them, they are most probably limestones. If they are softer and have a sugary texture, they are probably marble. Any kind of rock can form clasts in a breccia or conglomerate.

Marble breccia

Limestone conglomerate

Do they all come from the same parent rock (monomict) or are they from a mixture of different rocks (polymict)?

Monomict breccia

Polymict breccia

How big are the clasts? Are they well-sorted, meaning they are all about the same size or are they poorly-sorted, meaning they are a mixture of different sizes?

Well-sorted breccia

Poorly sorted breccia

Do the clasts touch each other, or is each one completely surrounded by the matrix?

Clast-supported breccia

Matrix supported breccia

Are the clast boundaries sharp and clear, or are they diffuse and hard to distinguish? Does it look as though the clasts are stitched or sutured together?

Sharp clast boundaries

Diffuse clast boundaries

sutured grain boundaries

What is the matrix like? Can you tell what it is made of?

The cement between the clasts is called the matrix. You can look for many of the same things in the matrix as you can for the clasts. For example, is it fine-, medium-, or coarse-grained? Are the grains well-sorted or poorly sorted? Does it contain any fossils or any interesting structures? Can you identify what minerals it is made of?

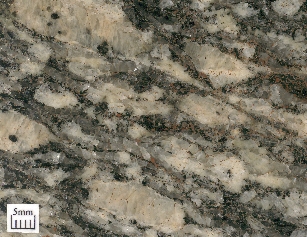

Remember… when a stone has a large pattern, small pieces can look very different even though they might be from the same slab.

The smaller samples all come from this one slab of breccia measuring 2 x 1m.

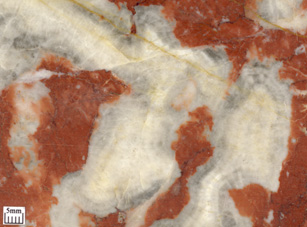

Banding and layering

Does the stone have any linear or circular banding? Are the layers composed of the same mineral or of different ones?

Linear banding is commonly seen when calcium carbonate precipitates from supersaturated water, either to form stalagmites and stalactites in caves, or to deposit a hot spring travertine. The coloured banding in many hot spring deposits consists of iron oxides that were deposited by bacterial action.

Linear banding in a travertine deposit

In other sedimentary rocks, linear coloured bands composed of different minerals often show where layers of different sediments were deposited on an ancient sea bed. When the rock has been metamorphosed, the layering may be folded or contorted by the extreme pressure.

Colour banding caused by layers containing different minerals

Another kind of banding is shown byagate, a very fine-grained variety of quartz with bands coloured by different impurities or minute gas bubbles. Veins of agate are commonly seen in jaspers.

Agate banding in a vein in jasper.

Banding is often seen in igneous rocks where heavier crystals have sunk in a molten lava, or where the flow of the lava has pulled crystals in a particular direction.

Circular banding of different minerals is shown by orbicular granites and diorites, and occurs as the molten magma cools, and crystals attach themselves in layers around central 'seed' crystals.

Circular banding in an orbicular granite

Are the clasts aligned in a particular direction or deformed in any way, for example sheared by metamorphic pressures?

When igneous rocks are metamorphosed, the pressure can align the newly formed crystals into layers. Rocks with layers of aligned crystals are said to be foliated.

Metamorphism shows in other ways, for example crystals, grains and clasts can be stretched or sheared by metamorphic processes. Rocks that show these textures are known as tectonites.

A foliated gneiss

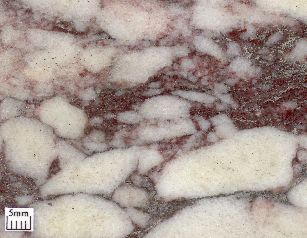

Sheared marble breccia

Veins and stylolites

Are there any veins crossing the stone? Are they wide or narrow? Are they randomly arranged or in a regular pattern? What mineral do they contain?

Veins are cracks or fractures in a rock that have been filled with minerals, often calcite ('spar') or quartz. They can be thick or thin, straight or curved, arranged randomly or in a particular pattern.

Straight white veins filled with sparry calcite

Reticulated (net-like) array of veins in serpentinite

Are there any thin wiggly lines called stylolites? What color are they?

Stylolites look like wiggly lines crossing the stone, rather like the trace on a graph. They form when a rock is compressed under the weight of more sediments and starts to recrystallise, part of an alteration process known as diagenesis. The stylolites contain all the clay, iron oxides and other impurities left behind, and so they are often a different colour from the rest of the rock.

Are there any stylolites, and if so, what colour are they?

A stylolite in a limestone. There is a thin straight vein running below it.

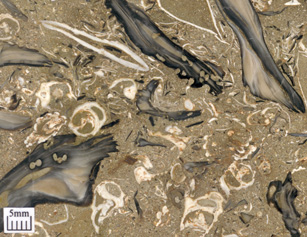

Fossils and other distinctive features

Does the rock contain fossils? How much of the rock is fossil debris? Are the fossils whole or broken up? Can you tell what they are?

In decorative stones, fossils most commonly occur in limestones. A limestone rich in fossils is known as lumachella.

A fossiliferous limestone

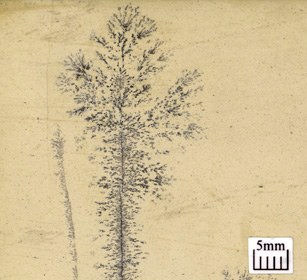

Are there any mossy, tree-like or shrub-like patterns?

These are called dendrites and are delicate tree-like growths, usually of iron or manganese oxides. They often form where chemical-rich solutions have penetrated slender fractures in a rock.

Dendrites in a fine-grained limestone

Dendrites in a travertine

Can you see angular areas of dark and light colour looking (with a bit of imagination) like the ruins of buildings?

This is the 'paesina effect' named after pietra paesina, an Italian ruin marble. It occurs where microscopically thin fractures in the rock are sealed with calcite, and restrict the spread of iron-staining by groundwater penetrating into the stone.

The 'pietra paesina' effect

Does the stone have nodules giving a rounded lumpy appearance?

Nodules can form around fossils, by the action of bacteria on the sea bed, and various other mechanism and are seen in some well-known decorative stones.

Nodular limestone

Are there any empty or filled-up cavities in the stone?

Cavities and voids are not usually a good thing in a decorative rock, and a porous structure that allows water to penetrate between the grains makes the stone far less durable. However a few decorative stones do have cavities and are still very durable. Sometimes the cavities are filled with a mineral such as calcite ('spar') or quartz.

Empty cavities where plant material has rotted away are a common feature of many travertines.

Cavities in travertine

Gas bubbles in volcanic rocks can also leave cavities called vesicles. If they subsequently fill up with crystals, they are referred to as amygdales.

Amygdales in a volcanic rock, filled with white crystals

Stromatactis is the name given to what appear to be irregular shaped cavities filled up with layers of white and grey calcite. They are found in certain limestones, usually of Devonian age. We are not certain how they form. They are perhaps the relicts of sponges or corals, the product of bacterial activity, or they are entirely inorganic sedimentary structures. It may be that they result from a combination of these causes.

Stromatactis in a Devonian limestone

Question Checklist

Colour

Is the stone the same colour all over (monochrome), or is it a mixture of different colours (polychrome)?

Crystals and grains

How big are the crystals or grains making up the stone? Are they all the same size? What shape are they?

Are the crystals or grains all the same mineral, or are they a mixture? Are they randomly mixed together? Does your rock have larger crystals in a fine-grained groundmass?

Looking at each mineral in the stone, can you identify it? Look at its colour and lustre, test its hardness and look at the shapes of any crystals.

Rocks within rocks

Is the stone composed of pieces or pebbles of rock cemented together? Are the clasts (the pieces or pebbles of rock) rounded or angular?

What kind of rocks are the clasts made of?

Do they all come from the same parent rock (monomict) or are they from a mixture of different rocks (polymict)?

How big are the clasts? Are they well-sorted, meaning they are all about the same size or are they poorly-sorted, meaning they are a mixture of different sizes?

Do the clasts touch each other, or is each one completely surrounded by the matrix?

Are the clast boundaries sharp and clear, or are they diffuse and hard to distinguish? Does it look as though the clasts are stitched or sutured together?

What is the matrix like? Can you tell what it is made of?

Banding and layering

Does the stone have any linear or circular banding? Are the layers composed of the same mineral or of different ones?

Are the clasts aligned in a particular direction or deformed in any way, for example sheared by metamorphic pressures?

Veins and stylolites

Are there any veins crossing the stone? Are they wide or narrow? Are they randomly arranged or in a regular pattern? What mineral do they contain?

Are there any thin wiggly lines called stylolites? What colour are they?

Fossils and features

Does the rock contain fossils? How much of the rock is fossil debris? Are the fossils whole or broken up? Can you tell what they are?

Are there any mossy, tree-like or shrub-like patterns?

Can you see angular areas of dark and light colour looking (with a bit of imagination) like the ruins of buildings?

Does the stone have nodules giving a rounded lumpy appearance?

Are there any empty or filled-up cavities in the stone?