Stephen Jarrett and how the Corsi collection came to Oxford

When the British Museum was in covert negotiations to buy Corsi's collection, Oxford geologist Dr William Buckland was one of those who wrote to the Museum's Trustees to recommend the purchase. The Trustees prevaricated. Meanwhile, a young student Stephen Jarrett braved winter weather to travel to Rome and buy Corsi's collection as a gift for the University of Oxford. What made Jarrett go on this journey, and why should a collection of marbles mean so much to him?

Jamaican fortunes

Stephen Jarrett, born in 1805, was the younger son of Herbert Newton Jarrett of Golden Grove, Jamaica, and his wife Anne1. Both sides of his family had long associations with Jamaica. Stephen's maternal great-grandfather was Thomas Wallen, a President of the Council of Jamaica. His paternal grandfather, John Jarrett, owned valuable Jamaican estates including Golden Grove, Silver Grove and Kent. John Jarrett returned in his later years to live at Freemantle House, outside Southampton. When he died in 1809, the Freemantle property was found to be heavily mortgaged and was sold for redevelopment. His Jamaican estates, some of the most valuable sugar plantations in the country, were inherited by his only son, Herbert Newton (Stephen's father), who also acquired properties in Marylebone, London, and in Nursling, Hampshire.

Herbert Newton Jarrett died just two years after his father, leaving the greater part of his estates and fortune to his elder son John. Younger son Stephen inherited the Guisborough (Guisboro) and Spring Garden estates in Jamaica2. Even as a child he had £400 a year at his disposal, although it is probable that a substantial part was expended in legal fees, a number of disputes relating to the estates being taken to the London courts for resolution. Stephen, John and their surviving sister Anne resided with their mother at her property, Camerton House, a short distance from Bath in Somerset. Both Stephen and John were to receive a privileged education first at Eton and then at Oxford.

The church in Jarrett's home village of Camerton

Stephen Jarrett came up to Magdalen College, Oxford in 1823, where he joined the ranks of the gentlemen commoners, very wealthy young undergraduates who in exchange for higher fees received such special privileges as dinner at the high table, and occupation of the finest rooms in college. They were not reading for Honours degrees, and to ensure 'study' did not detract from their preoccupations with pleasurable pursuits - hunting, shooting, wining, dining and gambling - these élite students would pay others of lesser means to write or embellish their weekly essays. Such was the antipathy towards academic study within the ranks that a few years later another gentleman commoner, John Ruskin, was informed by his peers he had committed 'grossest lèse-majesté against the order of gentlemen commoners' by writing an essay of such merit that he was asked to read it aloud in Hall3.

Negotiations

Jarrett travelled to Rome during the Christmas vacation of 1826, and at the beginning of January 1827, he visited Corsi to buy his collection of marbles as a gift for the University. He asked Corsi to bring the number of specimens to 1,000 and offered to have the Supplementary Catalogue printed at his own expense4. Corsi agreed to the sale; accepting a much more generous offer than another he had recently received.

A month earlier, Sydney Smirke, architect to the British Museum was carrying out covert negotiations on behalf of the Keeper of Mineralogy, Charles Konig, to buy the collection for the Museum. Smirke said it was for 'his friend in the country' and he drove a hard bargain. Corsi responded:

'Nonetheless, you ask me if I would be happy with £500 without the English stones and without the books. ... I think we can easily come to an agreement on the English stones. Lord Compton has told me that it is not easy to get them over there unless from the Duke of Devonshire, and that even receiving them as a gift, the work alone would cost more than I am selling them for. Such stones separated from the collection, are of little interest and I therefore intend them to stay together with the collection. ... I deal in Roman scudi without concerning myself with the gain or loss of the exchange from sterling. If you, or some bookseller, wishes to acquire the 250 copies of the catalogue then we could add to the previously mentioned sum another 150 scudi ... . I assure you that whoever sees the collection buys the catalogue; that the work is all new; that it has cost me a lot of hard work and that it deserves public acclaim. I inform you finally that I do not undertake anything else, that delivery and packing of the stones are all at you friend's expense ...' 5

Initially the Trustees declined the purchase6. Konig canvassed support from others, including Dr William Buckland, Reader in Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Oxford, who had seen Corsi's collection during his wedding tour of 1826. Buckland wrote to the Museum Trustees:

'... I have no hesitation in saying that it is quite unique in its kind, and such as is never likely to be made by any other individual, that it is in the highest degree interesting not only in an Geological and Mineralogical point as affording splendid 6specimens of the most beautiful rocks existing, but also as illustrating the History of the Arts both of Ancient and Modern Times, by containing a specimen of almost every known stone (including Granites, Marbles, Porphyries, Jaspers and Serpentines etc. ) that have ever been applied to the purposes of ornamental architecture or sculpture. ... I cannot think it too dear at £700 'M. Corsi showed me a Statement of what the specimens had actually cost him, and this was I think about £500 ...'7

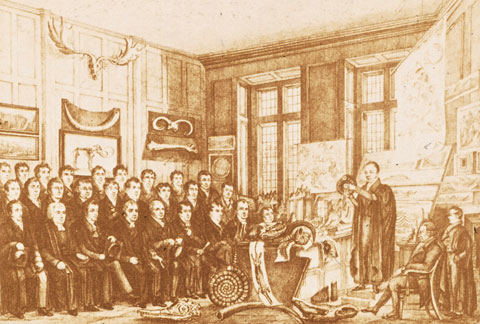

Dr William Buckland lecturing in the University

At their meeting in February 1827, unaware that Jarrett had already bought the collection, the Museum Trustees changed their minds and approved the purchase8. Konig was to be disappointed.

Motives and rewards

Although Dr William Buckland and Stephen Jarrett were not members of the same college and Jarrett did not attend Buckland's lectures,9 it appears they both had motives for acquiring the Corsi collection for Oxford. Buckland, like Charles Konig, was an enthusiastic collector, to the extent that by 1830 the geological collections had outgrown the available space in both the Ashmolean Museum and his rooms at Christ Church, and new rooms in the Clarendon building were provided for their accommodation10.

Stephen Jarrett may have developed a penchant for fine marble from his grandfather. When John Jarrett purchased Freemantle House, he employed fine Italian marble for its decoration, as Prosser describes:

'the entrance hall is ornamented with marble columns… The drawing room is ornamented with an elegant statuary marble chimney piece, brought from Italy by Mr Jarrett; the design is taken from an ancient sarcophagus, now in the gallery of the Capitol at Rome… The dining room, thirty-two feet by twenty-one feet, has its wall lined entirely with Italian marble (which Mr Jarrett effected at very considerable cost) and contains a massive side-board of verd antique.' 11

Here, he hosted fine dinners, welcoming the Prince Regent among his guests12. It was a room that his grandson would have heard about and perhaps seen. Many years later it was still a subject of pride within the family13. Stephen Jarrett had the financial resources to emulate his esteemed elder relative by investing in fine marble, a youthful sense of adventure, and aspirations for the kudos enjoyed by benefactors to the University. To Buckland, he was perhaps the ideal candidate for a mission to Rome to purchase Corsi's collection.

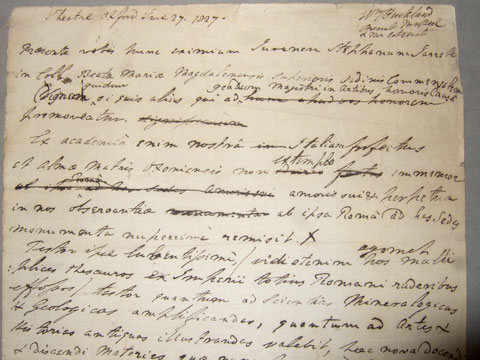

Jarrett's donation of the collection and catalogues was accepted by the Hebdomedal Council of the University on 5 February 182714. Buckland was instrumental in arranging the award of an Honorary degree of Master of Arts to Jarrett, 15conferred the following June, and his hand-written draft of the graduation oration praises the student 16.

Buckland's draft of his oration given at the presentation of Stephen Jarrett's honorary MA degree.

It appears Jarrett did not know the Trustees of the British Museum had initially refused to purchase the collection; but he knew he was bidding against that institution, evident from an account by the Rev. John Skinner, Rector at Camerton, of a conversation in which Jarrett was asking for a recommendation to become a Member of the Society of Antiquaries:

'...he thought he had a claim on the Antiquarian Society, because he had purchased the ancient marbles at Rome and presented them to the University, on which account he had received an Honorary Degree of Master of Arts... I then said, I had heard of him having presented some Marbles to the University, and imagined at first, they were ancient sculptured figures? Oh no! he said, infinitely more curious in a Geological point of view. They are patterns (of the size of bricks) of all the Marbles employed by the Romans in their superb works... I said I ... should like to look [the catalogue] over, in order to give me some idea of what his present was. Oh! said he, it is indeed a valuable one: the British Museum wished to obtain it, and sent out agents for the purpose; but I outbid them. What, I asked, was it put up to Auction? Oh yes! we bid hard against each other, and I got it: there are no less than a thousand feet of Marble; and the great difficulty at present is to know what to do with it. I said, I supposed it might make a fine Pavement for some of the Public Rooms at Oxford? Oh! it is infinitely too valuable for a Pavement; and the Geologist ought to have an opportunity to examine separately every piece, which he could not do if it became a fixture... I said, it must have been an expensive purchase. Oh! you may imagine I did not get it for as many pounds as there are feet. I am to understand then it cost you above £1000? Oh yes! a great deal more; but I did not grudge the money as it was so great a national benefit: and from what he said it appeared he thought that his having bought it over to the Country intitled him at once to become a member of the Antiquarian Society. 17'

The size of the stones appears to expanded markedly in Jarrett's mind, and if he did pay over £1,000 for the collection, Corsi must have been well-pleased indeed for the British Museum were offering about half that figure! Jarrett goes on to say he expected a visit from Buckland to Camerton that September, but the Rector, far from enamoured with the 'pretended Science, alias Humbug which the young people have derived from the Lectures of the good natured Professor', declined to meet him. In response to Jarrett's request for a recommendation, Skinner wrote 'I would just as soon recommend my Donkey...' and Jarrett never did achieve the membership he sought.18

Stephen Jarrett's later years

Jarrett was given special dispensation to remain at the University for a further year19, during which time he edited a new edition of the 1743 treatise on antique marbles by Blasius Caryophilus, sixty copies of which were privately printed in 189320. Aspiring to continue as a benefactor to the University, he called to see Skinner in 1829 with a list of coins which 'the University of Oxford wished him to procure for them. They are all of the scarcest kind. I gave him a silver Honorius, which was on the list.'21If any coins were ever sent to Oxford there is no record of their accession into the numismatic collection of the Ashmolean Museum22.

In the years when Jarrett was up at Oxford, Skinner wrote deprecatingly of him as an 'upstart' 'so excessively insolent', that he had 'all the curiosity of his mother without her tact'23. But in 1829 his feelings had modified. 'I think his manners are much altered for the better. Adversity is a great tutor, and he has experienced losses in his West India property, which may be of real benefit if it teaches him humility, as well as a determination to employ his own talents, and rely on his own resources more than on uncertain wealth.'24 In 1829, following the death of his mother, and the succession of his elder brother to the Camerton property, Jarrett moved to Nursling in Hampshire where he died, unmarried, in 1855. His niece remembered her late uncle kindly 'He was a great scholar & a man of polished manners & high culture & wd be very likely to present such a collection [of marbles] to his University.'25

1 Biographical information about members of the Jarrett family comes from A. Kerr-Jarrett's Orange Tree Valley website (http://www.orange-tree-valley.co.uk); Jarrett family papers held in the Somerset Record Office, Taunton, Somerset; Eton School, (1864), The Eton School Lists 1791-1860, 2nd edition (E.P. Williams, London) 104; Foster, J. (1888), Alumni Oxoniensis: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886 vol.2 (London: Joseph Foster); and inscriptions in St Peter's Church, Camerton.

2 Stephen Jarrett Esq. In accot. Currt. with the Trustees of John Jarrett Esq. deceased; and other Jarrett family papers in the Somerset Records Office, Taunton, Somerset.

3 The incident and the status of gentlemen commoners is described by Batchelor, J. (2000), John Ruskin: No Wealth but Life (Chatto & Windus, London), 33-37.

4 Corsi, F. (1827), Supplemento al Catalogo Ragionato d'una Collezione di Pietre di Decorazione formata in Roma... e posseduta dall' Universita di Oxford.(Da'Torchj del Salviucci, Roma), 3-4.

5 Ms; Letter from F. Corsi to S. Smirke, November 18, 1826. Min. Dept. archive, file DF 10/41-1, NHM; trans. (from Italian) McKay.

6 Ms; Minutes of the Meeting of the Trustees of the British Museum 11 December 1826.

7 Ms; Letter from W. Buckland to C. Konig, December 2, 1826. Min. Dept. archive, file DF 10/41-2, NHM.

8 Ms; Transcript of the Minutes of the Meeting of the Trustees of the British Museum 10 Feb 1827.

9 Ms; lists of attendees at Buckland's lectures, 1814-1849 OUMNH Archive, Buckland papers misc.mss 13.

10 Simcock, A.V. (1984), The Ashmolean Museum and Oxford Science 1683 1983. Oxford: Museum of the History of Science, 14.

11 Prosser, G.E. (1833-1839), Select illustrations of Hampshire J.A. Arch, London (unpaginated). The marble room was completely destroyed when Freemantle Hall was pulled down around 1852. The story of Freemantle Hall is given in Leonard, A.G.K. (1989), More Stories of Southampton Streets. Paul Cave Publications Ltd., Southampton.

12 A. Kerr-Jarrett Orange Tree Valley website (http://www.orange-tree-valley.co.uk) accessed February 2012.

13 John Jarrett's marble décor was remembered with pride some 75 years later by Stephen's niece: ms; letter from Miss Jarrett to Col. Stanier Waller, 22 October 1901. OUMNH Min.Colls.archive Corsi/016, Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

14 Ms; Minutes of the Hebdomedal Board, University of Oxford, for 5 February 1827; transcript by H.E. Bowman. OUMNH Min.Colls.archive Inst/87, Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

15 Ms; Journal of Rev. J. Skinner, Rector of Camerton, 10 July 1827. British Library Add MSS 33698.

16 Ms; Draft of oration. OUMNH Archive, Buckland Papers lecture notes box 1(10); trans. (from Latin) Glare.

17 Ms; Journal of Rev. J. Skinner, Rector of Camerton, 10 July 1827. British Library Add MSS 33698.

18 A. MacGregor pers. comm.

19 Ms; Minutes of the Hebdomedal Board, University of Oxford, for 12 November 1827; transcript by H.E. Bowman. Min.Colls.archive Inst/87, Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

20 Garofalo, B. (Caryophilus, B.) (1828), De antiquis marmoribus opusculum cui accedunt dissertationes iv, 2nd edn; ed. S. Jarrett. Oxford: Privately printed by S. Collingwood in 1893. A ms note by H.A. Miers, Mins.Colls.archive CORSI/021, Oxford University Museum of Natural History, notes that only 60 copies were printed.

21 Ms; Journal of Rev. J. Skinner, Rector of Camerton, 11 January 1828. British Library Add MSS 33698.

22 A. MacGregor pers. comm.

23 Ms; Journal of Rev. J. Skinner, Rector of Camerton, 15 Aug 1828, 10 Juy 1827, and 4 Sep 1828, British Library Add MSS 33698. It should be noted that John Skinner was himself a very unhappy and irascible man who depended on the Jarrett family as his patrons. At that time he believed they were trying to oust him from his position in favour of Stephen's brother-in-law, Mr Gooch. For published extracts of the diary, see Coombs, H. & P. Coombs (eds.) (1971), Diary of a Somerset Rector 1803-1834. Bath: Kingsmead.

24 Ms; Journal of Rev. J. Skinner, Rector of Camerton, 15 September 1829. British Library Add MSS 33698.

25 MS letter from Miss Jarrett to Col. Stanier Waller, 22 October 1901. op.cit.