The Corsi collection in Oxford

Corsi's collection arrived in Oxford to much publicity and was housed in purpose-built cases in the University's science library. When the library moved to the new Museum of Natural History, the collection came too, but it was left neglected in a gloomy upper gallery. The collection was rescued from obscurity by the combined efforts of Henry Miers, the new Professor of Mineralogy, and Mary Porter, a gifted young volunteer.

When word reached Oxford that student Stephen Jarrett had been successful in his bid to buy Faustino Corsi's collection of decorative stones for the University, Dr William Buckland was quick to circulate a press release. During February, March and April 1827, announcements appeared in journals as diverse as The British Critic, Quarterly Theological Review and Ecclesiastical Record; The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, etc; The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle; The Christian Remembrancer; the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal; and Jarrett's family's local newspaper, the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette1.

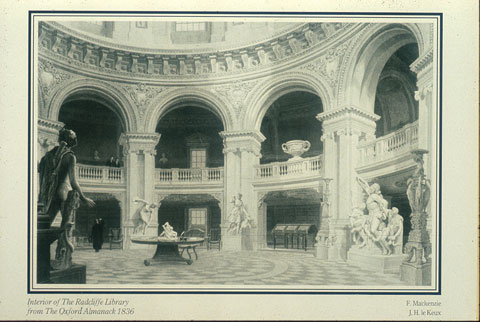

The collection arrived in Oxford in November 1827. Initially, it was suggested that it should be displayed in the picture gallery at Christ Church, the college where Buckland was Canon. However Buckland considered the lighting to be too poor for viewing the samples and proposed instead the Radcliffe library, a science library for the use of Members of the University2. The Trustees of the Library approved the construction of two new display cases to house it. For the next 25 years, the stones were displayed in the beautiful domed Radcliffe Camera, one of the highlights mentioned in guidebooks of the time. The cases are shown in an etching of the library interior in the University Almanack for 1835.

The two Corsi cases in the Radcliffe Library from the University of Oxford Almanack of 1835.

Splitting and sharing

As early as 1831, the Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, James Duncan expressed his support for the idea that the Corsi specimens should be sliced in two and half the samples to be given to the British Museum3. However he pointed out that both the University and the benefactor, Stephen Jarrett, might have reservations about any such scheme. In his letter to Charles Konig, Keeper of Mineralogy, Duncan also expressed his belief that the entire collection should be given to that institution in order that it should be seen by larger numbers of visitors; evidently he was keen to ingratiate himself with the London museum. The Radcliffe Librarian, George Williams did not offer any support to Duncan and Konig, and the scheme was dropped.

Again, in 1899, the great marble hunter William Brindley proposed to take slices from the specimens4. In exchange for the slices, he would produce a book of illustrations, and he had a plate of verde antico made as an example. This evidently did not have the support of University authorities, and the specimens remained intact.

An abandoned collection

In 1855, the University introduced a new Natural Sciences degree, and in response to pressure for a building that would bring together all the science collections, teaching and research into a single building, work commenced on the construction of the new Oxford Museum. The fine neo-Gothic building, with its glass-roofed courtyard, opened in 1860. The Radcliffe library books were transferred to new rooms along the front of the Museum. Corsi's collection was placed in its cases on the Museum's rather gloomy upper gallery; effectively abandoned by the library, yet not part of the Museum's collections either. The architect Sir George Aitchison wrote in 1884 that it was, 'needing cleaning and new labels. It was in the upper gallery inconvenient to students and visitors'5. He wrote at least two letters pointing this out to Sir Henry Acland, the Radcliffe Librarian.

Renewed interest

Three events were to rescue the Corsi collection from a downward spiral of neglect. The first was the appointment of Henry Miers as the first full-time professor of Mineralogy at the University. Miers was a gifted scientist, curator and administrator, who had studied classics as an undergraduate at Oxford. It seems he quickly took the Corsi collection in hand, searching out all the blocks that had gone missing (some of which had reportedly been used as door stops), and finding out more about the specimens. He sought the opinions of William Brindley, the leading expert on marbles of his time, writing in November 1899, '... I am anxious to make this collection one of real use as a reference series'6. Brindley was one of the major suppliers of stone of his time and was responsible for rediscovering and reopening a number of ancient quarries.

The second event, in 1901 was the opening of a new Radcliffe science library next to the Museum. When the books moved out, Corsi's collection was left behind, to at last become officially a part of the Museum's collections. It was clearly a very welcome addition to Miers's area of responsibility.

The third event was the arrival in Oxford of a teenager with a particular interest in decorative stone. Mary Winearls Porter had spent some years in Rome while her father had been a Times reporter there, and had met Giacomo Boni and Conte Gnoli, archaeologists working on excavations of the Roman Forum who had fired her enthusiasm for coloured stone7. Moving to Oxford, she already knew about the Corsi collection. Miers, quick to spot her interest and talent, set her to work, translating Corsi's Catalogo ragionato into English, and reorganising the collection for new displays. A geological arrangement according to the system of George Merrill8, used in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, was considered most appropriate.

Mary Porter's interest in the collection grew, and her research notes rediscovered in the 1990s show that she had spent considerable time identifying the coloured marbles used in the churches, colleges and public buildings of Oxford. She started contacting stone suppliers to build the Museum's decorative stone collections, getting many of the samples cut to the same dimensions as those of Corsi. As she learnt more about ancient marbles, she drew together her researches in a small book called What Rome was built with9.

Under the tuition of Henry Miers, Mary Porter started to study crystallography, and following Miers's departure to the University of London, little further work was carried out on the Corsi collection for several decades. Despite requisition of the Museum for troops use during the Second World War, the stones remained safe.

Mary Porter returns to Oxford

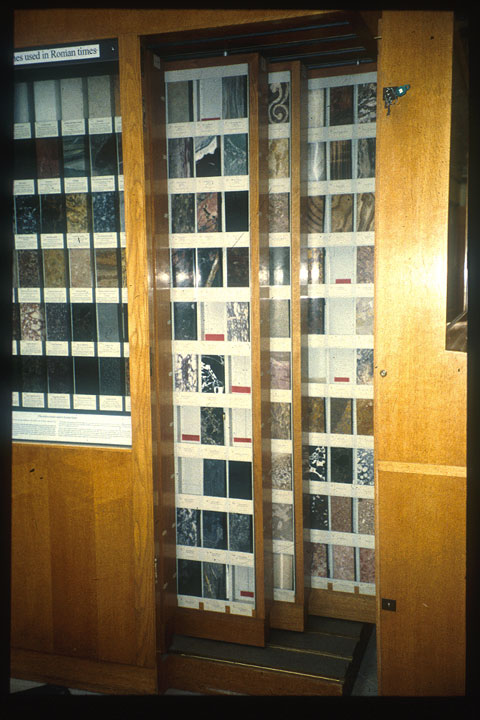

After some years carrying out crystallographic research in Germany and the USA, Mary Porter returned to Oxford in the 1960s as a Research Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall. Once again, she found time to work on the decorative stone collections. She gave instructions for the labelling of decorative stones in some of the older petrological collections of the Museum, and she reviewed the display of the Corsi collection. It was decided that a new case would be built, designed to store the slabs in pull-out racking that would make them readily accessible under the good daylight of the Museum's glass-roofed courtyard. A selection of samples would be displayed in glass cabinets on three sides of the new case.

The storage and display case built for the Corsi collection in the 1960s.

Porter now acknowledged that Merrill's arrangement was not particularly suitable for the Corsi collection and returned it to that of the Catalogo ragionato. She illustrated her displays with photographs of the stones used in monuments and statuary, and with samples of Egypian 'alabastri' and cosmati pavement.

Research visitors

The new Corsi displays were timely, for interest in ancient stone was growing. Visitors between 1964 and 1966 included Raniero Gnoli, the grandson of Conte Gnoli; John Ward-Perkins, the Director of the British School in Rome, and Oxford archaeologist Michael Balance. All were at the forefront of research into the ancient trade in marbles, and the rediscovery of ancient quarries. Gnoli's authoritative work Marmora Romana of 1971, which replaced Corsi's Delle pietre antiche as the leading reference on the subject of ancient stone, gave Corsi's collection welcome publicity. Interest in ancient stone has continued to grow, particularly by members of ASMOSIA, the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stone in Antiquity.

The Corsi Project

In the 1980s archaeologist Lisa Cooke started a placement working on the Museum's historic rock collections. She became particularly interested in the history of Corsi's collection and his Catalogo ragionato, preparing a new translation that corrected a number of errors made by Mary Porter. Assistant Curator Monica Price had also started reviewing Corsi's data about the specimens, names, geological descriptions and localities. It was evident that Corsi's collection was important both for its 'modern' and its 'ancient stones' and their paper at the ASMOSIA conference in Boston in 1998 outlined its history and significance10.

A cataloguing grant from the Jerwood Foundation in 1999 enabled the digital imaging of the collection which would facilitate research, and in particular, comparison of Corsi specimens with those in other collections. Expert visitors to the collection, such as Professor Lorenzo Lazzarini of the University of Venice, Professor James Harrell of the University of Toledo, Ohio, and Ian MacDonald of McMarmilloyd Ltd, have also enriched our knowledge of the collection. Professor Jim Kennedy, Dr David Bell and other geologists working in the University have helped provide hand specimen geological descriptions, making the collection more useful as an identification aid.

The number of visitors to use the Corsi collection has grown steadily. They range from archaeologists, architects and antique dealers, to conservators, artists and craftsmen. Monica Price's book Decorative Stone: the complete sourcebook11, published in 2007, features selected Corsi and other decorative stones from the Museum's collection.

Going online

A fully illustrated catalogue of the entire Corsi collection would be highly desirable but prohibitively expensive. Instead, the internet has offered us a way to make Corsi's collection and its Catalogo ragionato freely accessible to a worldwide audience. This website has been designed in collaboration with the Oxford University Computing Services Web Design Consultancy during 2011-12, and we are very grateful to the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation for their grant which has made this possible.

The project continues, and we welcome feedback and further information about Corsi's decorative stones.

1 The British Critic, Quarterly Theological Review and Ecclesiastical Record (vol.1, 546), The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, etc. (no.528, 141), The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle (new ser. vol. 20, 159), The Christian Remembrancer, or, the Churchman's Biblical, Ecclesiastical, & Literary Miscellany (vol.9, 184), the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (pt3, 173), and the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette (22 Feb 1827).

2 Ms; letter Dec 1827 William Buckland to the Vice Chancellor. Bliss Manuscripts, British Library Add MS 22574-22610.

3 Ms; letter 28 Feb 1831, James Duncan to Charles Konig. OUMNH Min archive Corsi/171.

4 Ms; letter 16 Jun 1899, William Brindley to Henry Miers , OUMNH Min archive Corsi/150.

5 Porter, M.W. 1973 The Diary of Henry Alexander Miers 1858-1942. Oxford: Privately printed at the Oxford University Press. 24.

6 Ms; letter 28 Nov 1899, H.A. Miers to William Brindley OUMNH Min archive Corsi/151

7 Porter, M.W. 1973, op.cit. 23-4.

8 Merrill, G.P. 1903 Stones for building and decoration, 3rd edition. John Wiley/Chapman &Hall, New York/London.

9 Porter, M.W. (1907) What Rome was built with : a description of the stones employed in ancient times for its building and decoration. Henry Frowde, London and Oxford, & New York

10 Cooke, L., and M. T. Price (2002), 'The Corsi Collection in Oxford', in J. J. Herrmann, N. Herz and R. Newman (eds.), ASMOSIA 5 - Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone. Proceedings of 5th International Conference, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1998, 415-420. Archetype Publications, London.

11 Price, M.T (2007) Decorative stone: the complete sourcebook, Thames & Hudson, London.