Faustino Corsi and his collection in Rome

The Roman Lawyer Avvocato Faustino Corsi (1771-1846) lived all his life in Rome where he was a highly respected judge. A family man, he enjoyed music and the arts, but he was most passionate about the decorative stones used by the ancient Romans, and his collection attracted many important visitors.

The young Corsi

Faustino Corsi was born on 15 February 1771, the son of Guiseppe Corsi, a circuit lawyer, and Angela (née Orsini). The young Faustino was a quick and receptive learner, and was sent as a boarder to the Ghislieri College, a school for lay boys taught by some of the leading intellects of the Collegio Romano. His education continued at La Sapienza University, where he studied law. During his student days he lived at home where he could easily avail himself of his father’s fine library of books on legal matters.

The lawyer

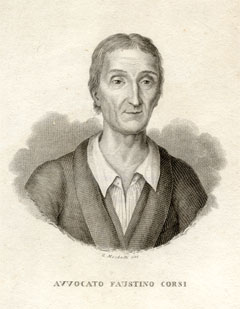

Faustino Corsi, from an engraving in the 1845 edition of Delle pietre antiche.

According to his biographer Pietro Biolchinii, Corsi was to gain a reputation as a wise and incorruptible judge, highly respected for his wisdom, eloquence, and dedication to justice. He practised at a time of ongoing political turmoil. Rome, invaded by Napoleon Bonaparte, came under French rule; the influence of the Papacy waxed and waned. Corsi appears to have thrived in this political environment, and records of the sales of national assets (mainly those of religious orders) between 1798 and 1799 show that although he had not bought properties or goods, he had entered into contracts with the French for perpetual leases of five housesii, indicating a considerable wealth. The political landscape offered him new intellectual challenges, and the interpretation of the law under French imperial rule was the subject of his first book, published in 1811: Il Testo del Codice penale ridotto a forma di dizionario… formata sulla traduzione italiana del Bolletino dell'Impero, n°277 bisiii.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, Rome returned to Papal control. Corsi, who was then listed as an investigating judge with the address ‘via dell' Angelo Custode, n. 25a’iv, was to become one of four heads of department, entrusted with responsibility for legal affairs. One who had long held Corsi in high esteem was Bartolomeo Cappellari, the abbot of the Camaldolese community of San Gregorio on the Caelian Hill. Cappellari was elected Pope Gregory XVI in 1831, and two years later he established a Ministry of Internal Affairs for Rome, appointing Corsi the First Clerk to the Ministry.

At home

Corsi was inspired by the use of ancient marbles in Rome, as here in the church of Gesù.

This may have been an onerous workload, but Corsi also made time for leisure pursuits. He was a family man, devoted to his daughter Elisabetta and her three young sons. Music featured prominently in their lives. Elisabetta was an accomplished pianist, singer and composer and her substantial collection of sheet music is preserved in the library of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Romev. It includes two of Faustino Corsi’s own musical compositions, O salutaris hostia and Quemadmodum desiderata. Corsi and his daughter took part in the Accademici Filarmonici Romani’s performances, for example in 1826 they performed in Felice Romani’s Maometto, set to music by Pietro De Wintervi. Another member of the chorus was ‘Paola Corsi’, who was perhaps Faustino Corsi’s wife. Corsi was also remembered for hosting recitals of the Psalms of Benedetto Marcello in his homevii.

The collector

Portrait of William Buckland engraved by Samuel Cousins, 1833, after the 1832 portrait by Thomas Phillips.

It was his interest in archaeology, and in particular the polished stones used by the ancient Romans, that is remembered today. In the first quarter of the 19th century Corsi built a collection of slabs of polished stones all cut to the same large dimensionsviii. This in itself was a challenge as many of the stones had only been found in small pieces. He first collected those used by the ancients, but then added stones from contemporary Italian quarries because they were not used by the ancients. He added a number of decorative minerals from other countries. He tells us he established relations with correspondents and friends in other cities to help him in his questix. In 1825, he had his carefully researched Catalogo ragionato published. In a letter to Sydney Smirke, Architect of the British Museum, he wrote Si assicuri che chi vede la collezione compra il catalogo, che l'opera è tutta nuova, che mi ha costato moltissima fatica, e che ha meritato il pubblico eloggio (‘I assure you that whoever sees the collection buys the catalogue; that the work is all new; that it has cost me a lot of hard work and that it has deserved public praise’)x. He was now living in a second floor apartment at 7A via di Santa Maria in Via, a short distance from the City’s main law courts in the Palazzo Montecitorio. It is likely that his visitors included the leading academics of the time as well as the young aristocrats visiting Rome on the Grand Tour. William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire was no doubt introduced to Corsi by his Italian agent Gaspare Gabrielli, who was an artist and dealer in rare stonesxi. Afterwards, the Duke presented to Corsi a number of samples of British stones, all cut and polished to Corsi’s specifications. Another visitor was Dr William Buckland, the Reader in Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Oxford, who came to Rome on his wedding tour in 1826. Appraised of the quality and value of Corsi’s collection, it was no doubt his suggestion that a wealthy young student, Stephen Jarrett, should obtain it for the University.

It is particularly significant that Corsi chose to organise his collection according to geological principles at a time when the study of geology was emerging to become a scientific discipline in its own right. Corsi was evidently well read and, guided by the works of French scientists such as Cyprien Prosper Brard, Alexandre Brongniart and Andre Brochant de Villiers, classified his stones according to mineralogical criteria. He subdivided classes according to the size and shape of grains or fragments. This was not without challenge, for the traditional views of thestone-cutters of Rome sometimes did not accord with the definitions of contemporary mineralogists. His work was of a strictly secular nature. Although Biolchini reminds us he was faithful to his Catholic religious upbringing, Corsi’s writings at no time call upon the agency of God to form any of the geological features he observes in his stones. For example, the plants, cliffs, trees and animals evoked by his dendritic and ruin marbles, he merely says were as if ‘...made to indulge Nature’s sense of humour’xii.

Stones with dendrites, as if ‘...made to indulge Nature’s sense of humour’.

Corsi made at least one other collection of decorative stones, this time of much smaller samples with less detailed documentation, inlaid into two table tops and now in the Natural History Museum, London.

Corsi’s later years

Archaeological excavations and engineering works both yielded a wealth of ancient stone as the 19th century saw the wholesale destruction and predation of many of Rome’s ancient villas to feed a frenzied international market in antiquities. After selling his collection, Corsi wrote at greater length on ancient stones in his Delle pietre antiche of 1828. As he continued his researches, this book went to two new editions, in 1833 and 1845xiii. They were to help stoke a voracious appetite for ancient stone, according to Ciranna, in her study of the Martinori family of scalpellinixiv.

Faustino Corsi developed a painful inflammation of the intestine which was to take his life on 28 December 1845. He is buried in the cemetary of S. Spirito in Rome. His study of ancient stone was to influence scholars for many decades to come.

i Biographical details largely come from Biolchini, P., (1846), 'Notizie biografiche intorno all'avvocato Faustino Corsi, romano' Giornale Arcadico di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti 108, 176-183.

ii De Felice, R. de (1960), La vendita dei beni nazionali nella repubblica romana del 1798-1799. Edizioni di storia e letteratura, Roma.

iii Corsi, F. (1811), Il Testo del Codice penale ridotto a forma di dizionario... formata sulla traduzione italiana del Bolletino dell'Impero, n°277 bis. Da' torchi di M. de Romanis e figli, Roma.

iv Dipartimento di Roma (1814) Annuario politico, statistico, topografico e commerciale del Dipartimento di Roma. Roma, Presso D. Rossi. Via dell'Angelo Custode was part of what is now the via del Tritone, according to the Roma Segreta website (http://www.romasegreta.it/via-del-tritone.html).

v Elisabetta Corsi Sabatucci's collection of sheet music includes her own compositions and arrangements, those of her father, and works by other composers, some bearing dedications to her. Catalogue records can be accessed through OPAC SBN (Catalogo del Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale). ( http://www.sbn.it/opacsbn/opac/iccu/free.jsp).

vi Romani, F and P. De Winter (1826) Maometto: melodramma tragico del Sig. Felice Romani posto in musica dal maestro Pietro de Winter: Eseguito dagli Accademici Filarmonici Romani l'autunno del 1826. Del' Accademia Anno V. (Dai Torchi di Antonio Boulzaler, Roma), 4.

vii Russo, P., (2004), Medea in Corinto di Felice Romani : storia, fonti e tradizioni (Firenze : L. S. Olschki) 34.

viii All approximately 145 x 73 x 40mm, substantially large than the 30-40mm square samples typically sold to tourists by the Roman scalpellini.

ix Corsi, F. (1825), Catalogo ragionato d'una collezione di pietre antiche formata e posseduta in Rome dall' avvocato Faustino Corsi. Da'Torchj del Salviucci, Rome p.6. His Supplemento al catalogo ragionato...Acquistata dal onorevole Signor Stefano Jarrett Ingleses, e posseduta dall' Universita di Oxford was published in 1827 and gives details of the last 100 specimens.

x Ms; Letter from F. Corsi to S. Smirke, November 18, 1826. Min. Dept. archive, file DF 10/41-1, NHM; trans. (from Italian) McKay.

xi Yarrington, A. (2009), '"Under Italian skies," the 6th Duke of Devonshire, Canova and the formation of the Sculpture Gallery at Chatsworth House'. Journal of Anglo-Italian Studies, 10, 41-62 ( http://www.chatsworth.org/files/italian_skies.pdf).

xii Corsi, F., (1825), op.cit. p.127, trans. L. Cooke.

xiii Corsi, F., (1828) Delle pietre antiche libri quattro. Da' Torchj di Giuseppe Salviucci e figlio, Roma ; 2nd edition (1833); 3rd edition (1845).

xiv Ciranna, S., (2007), I Martinori : scalpellini, inventori, imprenditori dalla città dei papi a Roma capitale Camera di commercio, industria, artigianato e agricoltura, Roma.