Why is the Corsi collection special?

Faustino Corsi's collection, with its 1,000 large samples of ancient and modern polished stones, is a remarkable resource for modern researchers. Corsi gave particular emphasis to recording quarry locations, and was one of the first to organise a decorative stone collection according to geological principles. His collection allows us to see exactly which stones he was referring to in his books, Catalogo ragionato d'una collezione di pietre antiche, and Delle pietre antiche, publications that were to be the most important reference works on ancient stone for nearly 140 years.

Size and scope

The tradition for collecting the stones used in antiquity, particularly in Italy, goes back to the 18th century or earlier. The oldest collections are often themselves exquisite works of art, small samples beautifully cut, perhaps edged in gold foil, or inset in boxes or tablesi. They were both works of art and symbols of learning. Stones might be arranged according to colour and markings, but often simply to make the collection as beautiful as possible. If there is any information at all about each stone, it is rarely more than the traditional name used by the scalpellini, the stone cutters of Rome.

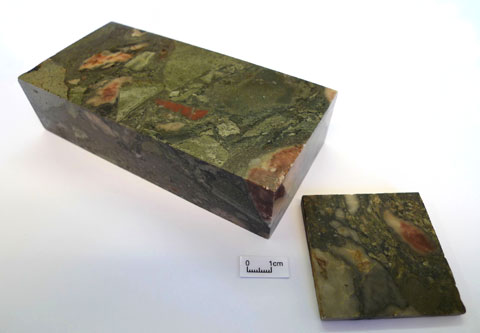

Corsi's collection was different. He sought large samples of each stone to show the features well. Each block was to be a uniform size, about 145 x 73 x 40 mm; polished on the top and sides. Corsi appreciated that the pattern of a stone may depend on the direction in which it is cut, and his chosen dimensions would allow him to see both top and side views. Where a particular stone showed diverse characteristics, Corsi wanted several samples to show the variation. He tells us he spared no expense to achieve these aimsii.

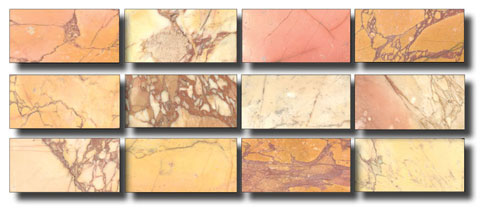

Corsi's specimens are large compared with the typical samples of 18th and early 19th century decorative stone collections (shown right).

Several examples of giallo antico from Chemtou, Tunisia, to show how it varies

Corsi kept encountering new stones, and as his interest grew, he started acquiring others, simply because they were not used by the ancient Romans. Faustino Corsi was one of the first to collect so-called 'modern' decorative stones. By adding those used in medieval, baroque and contemporary architecture of Rome, Corsi had inadvertently made his collection even more unusual and special. It is one of very few such collections preserved in museums today.

A geological arrangement

Corsi's collection is also special because he chose to arrange the stones in a geological order. In his Catalogo ragionato, he divided his collection into classes according to their mineral composition. He added observations on the texture, grain size, lustre, and fracture of the stones; the nature of any veins and brecciation, and the presence of particular fossils, all features that are fundamentally important for helping to distinguish one stone from another.

He started off with 'marmi', the marbles, and explained how mineralogists would use this term for rocks composed of carbonate of lime and capable of receiving a polish. This definition includes limestones as well as the 'true' marbles of modern geologists, but his approach is practical for one not equipped with a petrological microscope, and his definition of marble largely accords with that of the modern stone trade.

After Corsi's marbles come other kinds of stone including gypsum, fluorite, slate, volcanic lava, serpentinite, jasper and agate, each in a class of its own. His porphyries are followed by 'graniti', the granites, another 'catch-all' term, used for igneous and metamorphic siliceous rocks by both Corsi and the stone trade today.

Marble collections made after Corsi's time generally follow his lead, with good sized specimens arranged in a geological order; take for example the Belli brothers' collections in the museums of Berlin, and La Sapienza University in Rome; the Belluci brothers' collection in Vienna, the Ravestein collection in Brussels, the fine collection of the Capitoline Museum in Rome, the De Santis and Pescetto collections of the Italian Geological Survey, and even the 20th century Watson Collection in Cambridge.

An influential collection

In his Catalogo ragionato, Corsi wanted to record where his stones were quarried, something that collectors of his time rarely did. His agents and acquaintances who supplied his 'modern' stones could in some cases provide detailed information about where they were extracted. The ancient stones were more problematic. These came from the ruins of Rome, and the locations of many of their quarries were no longer known. Corsi took the 'traditional wisdom' of the scalpellini, and attempted to correlate his stones with those described by Pliny, Theothrastus and other authors of antiquity.

Having sold his collection and remaining copies of the Catalogo ragionato to Stephen Jarrett, Corsi went on to write a book Delle pietre antiche which went to three editions between 1828 and 1845iii. This was to be the principal reference work on ancient marble for nearly 140 years, until Raniero Gnoli wrote Marmora Romana in 1971iv. His collection lets us see exactly which stones he was referring to in his books. Many of the ancient quarries have now been rediscovered, sometimes confirming Corsi's conjectures, and sometimes refuting them. However the repetition of his mistakes in relatively modern times is indicative of his long-standing influence.

By correcting and updating his information about the stones, we are able to make his collection a valuable reference tool for today's researchers.

In the 1890s, when Felix Karrer was cataloguing the fine collection of ancient marbles supplied to the Naturhistorischen Museum in Vienna by the Belucci brothersv, he obtained locality data from Corsi's books.

i De Nuccio, M., Ungaro, L., et al. (2002), I marmi colorati della Roma imperiale. ed., Marsilio, Venezia.

ii Ms; Letter from F. Corsi to S. Smirke, November 18, 1826. Min. Dept. archive, file DF 10/41-1, NHM; trans. (from Italian) McKay.

iii Corsi, F., (1828) Delle pietre antiche libri quattro. Da' Torchj di Giuseppe Salviucci e figlio, Roma ; 2nd edition (1833); 3rd edition (1845).

iv Raniero Gnoli (1971) Marmora Romana (Edizioni Elfante, Roma). This authoritative book was the first systematic study of ancient Roman marble since Corsi's time.

v Karrer, F (1892) Führer durch die Baumaterial-Sammlung des K.K. Naturhistorischen Hofmuseums (R. Lechner's k. u. k. Hof- und Univ.- Buchhandlung , Wien).