Class I

Marbles (Marmi)

[p11] The word 'lapis' for Latin speakers was generic, as the word 'stone' is for us, and by it they were indicating those solid minerals impervious to water and not among the bitumens, sands, or metals. Later they used to indicate by 'marmora' all decorative and ornamental stones which would take a fine polish when cut, inferring the etymology of this name from 'μαρμαίρον' which means 'to shine' in the Greek language. From this basic premise they did not distinguish any of the materials, and they indiscriminately called 'marbles' the calcareous earths, serpentines, gypsums, basalts, granites, porphyries, jaspers, and any other stone, as often as they did the calcareous rocks. Finally, mineralogists recognise as marbles only those stones composed of calcium carbonate which are susceptible to taking a polish.

[p12] I warn readers that when referring to the various kinds of marble I shall not repeat that each one is formed of the same substance, that they are soft to cut, that when struck by steel they do not give off sparks, and that their colours are fortuitous and generally speaking products of the combination of metallic substances.

Section I

Monochrome marbles (Marmi unicolori)

Monochrome marbles are looked upon as the easiest to recognise, as much because of their unity of tint as because of their regularity of formation, and therefore I begin the description with them, keeping as methodical an order as possible.

Species I

Statuary marbles Marmi statuari

[p13]

The ancients preferred white marble for the sculpting of statues, busts and herms, as well as for the relief carving of architectural embellishments, for facings on buildings, and for mortuary urns. For architectural features Carrara marble, then called Lunense, was most commonly employed in Rome as the stretch of water was short, and it used to be transported at very moderate cost. For the sculpting of statues, on the other hand, use was usually made of Greek marbles or those from the vicinity of Greece, though the carving may have been executed in Rome. When discussing these marbles only the different degrees of whiteness and the varieties of grain and texture can be observed. So that it may be possible for each marble among the examples in the collection, to be seen at their best in the public museums I shall mention the most famous statues that are made of each one.

The provenances for white marbles suggested by Corsi are not always reliable. The traditional petrographic study of grain and texture to which Corsi refers can indicate possible provenances, but nowadays this is augmented by a combination of techniques, for example trace element and isotopic analyses, which together enable scientists to pinpoint the quarry location with rather greater certainty.

Varieties

1. (14.1) Marmo greco duro. Marmor Parium. Strabo 1 reports that Parian marble, so very well known among the ancient authors, was taken from the island of Paros in the Greek Archipelago, and precisely from monte Marpesso noted in the verses of Virgil. Generally it is believed that is would have been of a very fine grain, but on the contrary it is formed of large, shiny scales. Pliny 2 wrote that according to Varro, Parian marble was called 'Lychnite', because as the seams were underground it used to be quarried by the light of oil-lamps. While I was talking about this passage in Pliny with the English gentleman Mr Dodwell 3 he kindly gave me his own admirable publication about his tour through Greece, in which he explains thus: 'The Parian marble quarries, as I have observed in the field, were never subterranean but cut down the side of a mountain and open to the glare of day; the word “lychnites” was given to the marble on account[p15] of its large, shining crystals and semi-transparent quality. Parian marble is mistaken for Pentelic nowadays, and vice versa.' Parian marble is generally gleaming white and rather hard to cut. The statue of the Minerva Medica in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museum is of Parian marble. (Rare).

Marpesia, now known as Marpissa, is north-east of Paros town (Parika). Corsi did not provide more than a general reference to Virgil, perhaps feeling sure that any reader of his work, being well-educated, would be familiar with it. There are at least two references to Parian marble in the Aeneid.

Edward Dodwell was an extensive traveller in Greece, who took a Roman artist, Pomardi, with him. His writings are somewhat reminiscent of Pausanias's Guide to Greece of c. AD150. He had settled and married in Rome, and was a fellow collector of samples of marble; of which 247, now in the Museo di Geologia, at the Università di Roma La Sapienza, are ancient stones i . He mistook absence of evidence for evidence of absence with regard to the Parian quarries; the finest quality, almost translucent, marble has been extracted from underground quarries since Roman times.

The name Greco duro refers to dolomite marble from Cape Vathy, Thassos, and as Corsi's specimen is dolomite marble, it most probably does indeed come from Thasos rather than Paros.

i. Bunsen (1837) 55-572. (15.2) Marmo grechetto duro. Marmor Porinum. The sample that I describe is of the same grain size, of the same hardness and of the same gleaming whiteness as Parian marble, except that this one is formed of scales that are a little thinner, and it is somewhat lighter in weight. It seems that this may be the marble 'Porino'. Pliny 4 who literally copied Theophrastus 5 says that marmo Porino, called thus on account of its lightness, 'is similar to Parian in colour and hardness'. Moreover, one should be aware that although Porino might resemble tufa in lightness, from which it takes its name, nonetheless it is compact and very suitable for sculpture. Plutarch 6 mentions a statue [p16] of a Silenus in marmo Porino; and in the Vatican Museum, of the same marble, is the famous so-called Belvedere Torso, a work of Apollonius the Athenian. (Rare).

'Poros lithos' was a term used in Antiquity to describe limestone, and today may include certain shelly sandstones. The term is not used by geologists, but sometimes others may refer to indeterminate stone as 'poros', especially that found in foundations of ancient buildings as at Epidauros i .

Corsi appears to have understood Theophrastus, who goes on to say that the Egyptians used it, according to the translation of Hill ii , 'in the partitions of their more elegant edifices'. Theophrastus is referring to high quality, white fine grained Tura limestone from quarries, deep, and possibly underground, on the eastern shore of the Nile south of Cairo 13-17 km from Giza. This formed the 'casing' or facing of the Great Pyramid, which was then highly polished to shine in the sun. At least since AD 1300 the stone was robbed and re-used, particularly in mosques and Arab fortresses iii , iv .

The tufa to which Corsi refers, is porous travertine; not a particularly compact stone. There are many Greek statues of limestone as well as of statuary marble, as may be seen in the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

The Belvedere Torso is part of a statue of a naked male, perhaps Hercules. The statue was much admired by Michaelangelo and other artists of Renaissance and Baroque periods.

i. Borghini (1997) 29ii. Theophrastus, tr. Hill (1746) 23

iii. Pliny, tr. Eichholz (1962) 92-93 comments

iv. Theophrastus, tr. Caley & Richards (1956) 73-74

3. (16.3) Marmo greco fino. Marmor Pentelicum. Gleaming white and of very fine grain is the marble known under the name of Pentelic (Pentilico) because, according to Pausanias 7 , it used to be quarried from Mount Pentelicus in Attica, near the city of Athens. Although it would often be used for columns and other architectural features, nonetheless it was also used to a great extent by the Greeks for statuary. Scopas and Praxiteles exercised their chisels a great deal on Pentelic 8 . In a letter to Pomponius Atticus, Cicero 9 thanks him for having sent many herms of this marble from Athens. There is a herm of the young Augustus in Pentelic in the Chiaramonti Museum in the Vatican. (Rare).

Both Scopas and Praxiteles were active between 370 - 330 BC, were often linked, and were much admired in Antiquity.

Cicero was writing to his friend Atticus, who like many Romans lived in Athens, asking him to arrange a shipment of statues and works of art that would be suitable for a lecture hall and colonnade. The idea of taking art works from an earlier culture had been in vogue long before the Grand Tour revived the practice among modern Europeans.

The 'Pentelic herms' had bronze heads. A herm is now generally understood to be a sculpted or cast head or bust mounted on a tapering square pillar: hence the modern practice of displaying busts on similarly shaped pedestals of decorative stone. Although the Herm of the Young Augustus was not considered of particular importance, it logically follows on from mention of the Attic herms.

The Chiaramonti Sculpture Museum founded by Pope Pius VII (1800-23) and named after his family, is in part of Bramante's 300m corridor of the Vatican Museums. Its displays include a 'fine collection of portrait busts of the Imperial period, sarcophagi , altars, and decorated architectural fragments' i , and was new when Corsi was forming his collection.

i. Claridge (2010) 4734. (16.4) Marmo cipolla. Marmor Hymettium. Following Pentelic I consider it opportune to talk about Hymettian (Imettio) because the quarries of the two marbles are so near each other [p17] many writers confuse them and their names are even interchanged. Among the Italian stonecutters it is called 'marmo cipolla' because when it is worked, an odour not unlike that of an onion is emitted. Mineralogists call it marmo greco fetido as hydrogen sulphide gas is released by brisk rubbing. The grain is of large scales, the colour is of a greyish white, verging on greenish, with veins of dark grey. The ancients knew it as Hymettian (Imettio), because as Xenofonte 10 says it was quarried from Mount Hymettus (monte Imetto), now called Trelo, in the vicinity of Athens. Generally it was employed in works of architecture, as may be seen in the superb supporting columns of the nave in the church of S. Maria Maggiore, and in another twenty columns that ornament the church of S. Pietro in Vincoli. Horace 11 says that it used to be used for architraves. It is often used by sculptors, and the very learned Visconti 12 noted that the celebrated Vatican Nile might be of this marble. The mountains of Hymettus and Pentelicon are so near each other, and to [p18] the city of Athens, that Vitruvius 13 says they are to be seen adjacent to the first wall of the city. It is precisely this proximity that has led to some equivocation among writers about these different marbles; their characteristics have been interchanged, and it is said not infrequently that Pentelic corresponds to marmo cipolla. Every doubt is resolved, however, by the account of the traveller Olivier 14 who visited the quarries of the Pentelic and Hymettian marbles. Speaking of Hymettian he explains thus: 'After passing the schistous layer forming the base of the mountain, one comes upon a marble white in some places, and in others a bluish grey mixed with a white very inferior to that of Pentelic marble. The stratum of Pentelic marble that immediately overlies the schists is white and of very fine grain'. (Common).

Latin poets often symbolize opulent extravagance by marble columns,

gold, ivory, and the best purple dye; here Horace

i

contrasts his own simple way of life with the indulgence in

luxury of his contemporaries:

'Carven ivory have I none

No golden cornice in my dwelling

shines;

Pillars choice of Libyan stone

Upbear no architrave

from Attic mines'.

In ancient Greece, Hymettian was generally used for buildings, especially columns and architraves. Pentelic, whiter and easier to work, was more usually used for statues, for particularly important temples such as the Parthenon, and for architectural embellishment such as pedimental sculpture; as was Parian (see no. 1). Columns in Greek temples were always load-bearing; during the 7th century stone had taken the place of tree trunks, as in the temple of Hera at Olympia. Decorative effects were achieved by painting in bright colours, and sculpting pedimental sculptures, friezes and other architectural features such as those of the three orders of architecture.

Olivier ii is describing the view from the peak of Mount Hymettos across to Mount Pentelicus, and to other points of the compass; Corsi paraphrases a passage in Nibby's Del Foro Romano iii and gives a different impression.

Much typically grey striped marble used since the AD 130s in Rome was Proconnesian iv , quarried on the island of Marmara, between the Dardenelles and the Bosphorus. It is now widely thought that Hymettian was often wrongly ascribed, perhaps including the 36 columns in the nave of S. Maria Maggiore. Collectors, and indeed some geologists, seem to have been unaware of this well into the 20th century. Both Proconnesian and Hymettian marbles are also known as marmo cipolla, giving off a fetid onion smell when cut, as does the grey striped calcite marble from the Greek island of Thassos, which may look similar. Ravestein's catalogue of the collection of ancient marbles in the Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire de Bruxelles v has several samples called 'marmo greco fetido'.

The 'Vatican Nile', known as the 'Colossus of the Nile', is a 1st century A.D. Roman sculpture, and is still in the Braccio Nuovo.

i. Horace 2.18, tr. Conington (1882)ii. Olivier (1807) v.6 451

iii. Nibby (1819) 24

iv. Claridge (2010) 41

v. Ravestein (1884) 625

5. (18.5) Marmo greco livido. Marmor Thasium. A statuary marble which, according to the authority of Herodotus 15 , was discovered by the Phoenicians on the Island of Thasos, in the Gulf of Contessa on the coast of Romania, [p19] and was called Thasian (Tasio) after the location of the quarry. Pliny 16 has not left us any historical account of this marble, except that it might be 'less bluish-grey than the Lesbian'. In fact, in the sample that I describe, the tint appears somewhat more bluish-grey than gleaming white and the grain is formed of medium-sized scales. This marble did not enjoy a great reputation at any time although Pausanias 17 assures us that the Athenians valued it and had two statues made of it in honour of Hadrian. The statue of Euripides in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museum, no. 81, is made of this marble. Belon 18 claims that the exterior of the pyramid of Caius Cestius might be of Thasian marble, but I think he was mistaken since it seems somewhat like Lunense. (Rare).

The island of Thasos (Thassos) lies in the Gulf of Strymonas, off the coast of the province of Kavala, East Macedonia and Thrace, in north-east mainland Greece. Thasian marble was exploited from at least the 7th century BC. Some is calcitic and may have grey streaks. The Romans quarried it extensively on the headland of Aliki. Dolomitic marble also occurs on the island and was quarried at Cape Vathy in large quantities. Statues of dolomitic Thasian marble are to be found in major museums. Both calcitic and dolomitic marbles are of medium grain size i .

The statues in Athens were outside the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The foundations were laid in 515 BC, but it lay unfinished until Emperor Hadrian had construction completed and a monumental arched portico built; it was dedicated in AD 131. Of 108 original columns 16 survive.

The New Wing, 'Braccio Nuovo' to which Corsi refers many times in this Catalogo ragionato was inaugurated by Pius VII in 1822, the year before he died. Consequently it was very topical when Corsi was writing. It is one of several Vatican museums, and opens off the sculture gallery known as the Chiarimonti Museum which was also founded by Pius VII (see notes for no.3).

Claridge ii confirms that the pyramidal tomb of Caius Sextus (Caius Cestius) mentioned by Bellon, which was built 18-12 BC, was faced with Luna (Carrara) marble.

i. Bruno (2002b)ii. Claridge (2010) 399

6. (19.6) Marmo greco scuro. Marmor Lesbium. The Lesbian marble (marmo Lesbio), which used to be quarried on the island of Lesbos, today Mytilene, is more like a bruise in colour than the Thasian, and almost tends towards light yellow. The grain is of very large, bright scales. Philostratus 19 observed that this marble, which among white ones could be said to be dark, was used by the [p20] ancients for the construction of sarcophagi in preference to other statuary marbles. Sculptors also made use of it, as shown by the beautiful statue of Julia Pia no.120 in the Vatican Museum and by the famous Venus in the Capitoline Museum. (Very rare).

Lesbos (Lesvos) lies just off the Turkish coast from ancient Pergamon (near modern Dikili); the major town, on the south eastern side of the island, is Mitilini.

Corsi describes this same stone here as 'dark … suitable for sarcophagi' and as 'yellowish'. In his Delle pietre antiche i he calls Lesbian marble marmo Greco giallognolo and reiterates this description: 'more bruised looking (piu livido) than the Thasian, and almost tends to yellow … sculptors probably recognized that it was well suited to the representation of flesh'.

In the early 19th century the Italian word livido could be interpreted in a number of ways, Baretti's dictionary for example gives 'livid, pale, wan, black and blue, disfigured' ii . In Latin it appears to be associated with blueness, and bruising, which may also show as yellow. 'Livid' in English has many meanings, including the lividity of death, which is similar to bruising and caused by the effect of gravity on blood in the small vessels. In Italian, in the context of marble, I [LC] believe that livido is now taken to mean the lustre of wax, which is how I have, perhaps anachronistically, sometimes translated it, though perhaps, as above, Corsi's meaning is closer to the Latin.

Marble from Lesbos, according to Lorenzo Lazzarini iii is always grey, sometimes rather dark grey, and sometimes veined with yellow. Gnoli iv discusses it with grey marbles. Although Corsi's description of this specimen covers both main features of marble from Lesbos, the sample itself is very white and does not show these features.

The statue known as Mattei Ceres, which among other names is known as, Julia Domna, is clearly the one to which Corsi refers. Julia Domna (d. AD 217), was the young Syrian second wife of the Emperor Septimius Severus (145-211). Silver denarii were struck in Rome 196-211 with IVLIA PIA FELIX AVG on the obverse. Her son Caracalla also struck denarii with IVLIA PIA on the obverse. The 'Capitoline Venus', a 2nd century AD work, a little above life-size and based on a Hellenistic sculpture, is now thought to be Parian marble v .

i. Corsi (1845) 85ii. Baretti (1807)

iii. L. Lazzarini pers. comm.

iv. Gnoli (1988) 179

v. National Gallery of Art, Washington (2011)

7. (20.7) Marmo greco turchiniccio. Marmor Tyrium. There is in my collection a piece of white statuary marble with large scales, rather hard to cut, and of a white verging on cerulean I used to be ignorant as to which name the ancients used, for they have left us very dry descriptions of statuary marbles. I noticed, however, that Papinius Statius 20 had mentioned a white marble that used to be quarried from Mount Lebanon in Phoenicia, and because of its proximity to the cities of Tyre and Sidon, today Sur and Saida, it was called indiscriminately Tyrian or Sidian marble (marmo Tirio, e Sidonio). I noticed that, according to the authority of Josephus Flavius 21 , Solomon constructed and Herod restored the Temple at Jerusalem with the white marble of Lebanon, and I concluded that the white marble used in [p21] that city, and in all of Syria, could not be other than Tyrian (Tirio) in the same way that all works of statuary marble seen in Italy are from the quarries of Carrara. In order to compare my specimen with some marble that might have come from Jerusalem I examined that of the Scala Santa and found it to be very similar. It is for this reason that I can believe, on good grounds, that the marble commonly called 'greco turchiniccio' might be the marble that the ancients used to call Tyrian. (Very rare).

In 2007, Israeli archeologists reported that they had discovered a quarry close to the Second Temple compound, that had provided King Herod with the 20 ton blocks of stone used in his rebuilding of that temple. The Romans levelled the site in AD 70, only leaving the western 'Wailing' Wall standing i . Perhaps Corsi recalls a Biblical description (1 Kings V) of Solomon using both cedar wood and a large work-force from Lebanon when building the temple, but not necessarily using stone from Lebanon.

Statius ii in this poem about the interior decoration of baths of the rich youth, Claudius Etruscus, discusses marble that is interpreted by some translators as from Tyre and Sidon [Lebanon]. However, many scholars, for example Frere iii , have said the text is mutilated or unclear. Mozley iv writes 'No amendation of the text is convincing here. It is not certain whether there is any allusion to marble of Tyre and Sidon, of which nothing is otherwise known'.

Corsi expands the corrupt text by Statius and makes a tentative deduction based on his own experience that was taken as correct by many people, whereas Gnoli v suggests that the alleged Tyrian marble never existed. The name Tyrian (Tirio) continued in use through the 19th century until the late 20th century. For example in the Borromeo Collection vi : '398. Marmo Tirio turchino'.

The Scala Santa was so-called after a medieval legend that the staircase, which had been the one that led to the balcony of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem and had been trodden by Jesus Christ on his way to condemnation, was brought to Rome by St Helena, the Christian Mother of Emperor Constantine. Now the steps are protected by boards, but still pilgrims climb on their knees to the Sancta Sanctorum where the most sacred relics from the old Lateran palace are preserved.

i. Gaffney (2009) 2ii. Statius (n.d.) Silvae 1.5.39.

iii. Statius, ed. Frere (1944) 44

iv. Statius, tr. Mozley (1928) 61, note d

v. Gnoli (1988) 37-38

vi. De Michele & Zezza ed. (1979) 91

8. (21.8) To another statuary marble of less fine grain, and less white, than Pentelic I dare not assign the location of the quarry, since I do not with certainty see it indicated by any writer. Vitruvius 22 mentions a white marble from Ephesus and another from Heraclea which were used in the temple of Diana. Strabo 23 speaks of another similar marble that was quarried near Mylassa, but not knowing the characteristic qualities of these marbles I am not sure that the specimen of which I speak appertains to any of them. I hope the reader [p22] will be more satisfied with my explanation than with an unverified yet confident assurance. The Venus of Bupalo in the Gabinetto of the Vatican Museum is of this marble. (Rare).

Dodge and Ward-Perkins i identify Ephesos and Heracleia under Latmos, both in Caria, (now part of western Turkey) as major quarries of white marble in the Roman world. Aphrodisias, also in Caria, is now recognized as the source of fine white marble, and is associated with a school of sculptors, though in Corsi's time neither quarry nor site had been rediscovered.

It is possible that the statue by Bupalo to which Corsi is referring may be the so-called Standing Venus.

i. Dodge & Ward-Perkins ed. (1992) 1529. (22.9) Marmo di Carrara. Marmor Lunense. Strabo 24 states that near the city of Luni, now Carrara, in Etruria, there were quarries of white marble equally suitable for the sculpture of statues as for architectural ornamentation. The ancients used it for both purposes. In the octagonal courtyard of the Pio-Clementino Museum a Bacchus of marmo bianco di Carrara can be seen; but it was more commonly used for columns and other ornamental features. The quarries of this marble are still open and supply all the studios of the sculptors, inlayers and stonecutters. The grain is fine like that of Pentelic marble; the colour is of a gleaming, soapy white, which is somewhat like majolica, as Sig. Nibby 25 observes, and often shows black spots caused by a mixture of metallic substances. There are many quarries of the statuary marble of [p23] Carrara; the best are called 'Crestola', 'Zampone', 'Bettolia', and 'Ravaccione'. (Very common).

The quarries were probably first opened under Julius Caesar, and greatly expanded and developed by Augustus i . The Etruscan town of Luna, since called Luni, within eight miles of Carrara, was in ruins by 1442. By the 19th century the site was one and a half miles from the sea. According to Jervis, 'The first mention of the word Carrara … [was in] AD 963.' ii . The quarries are still working today.

It is very probable that Corsi meant Betogli for 'Bettolia'.

The Octagonal Courtyard, built after a design by Bramante and altered in 1775 with recesses (gabinetti) in the corners by Simonetti, is one of fifteen lavishly decorated spaces of the Pio-Clementino Museum in the former Belvedere Pavilion of the Vatican. There are many representations of Bacchus (Dionysus) in the Vatican.

i. Dodge & Ward-Perkins ed. (1992) 22 footnoteii. Jervis (1862) 5

10. (23.10) Bianco di Pont. This marble, which is found in Piedmont, is inferior to that from Carrara, but nonetheless good use can be made of it for architectural ornaments and also for sculpture. The colour tends to bluish-grey, like that of the Thasian of the ancients but it is less like it in grain, which is fairly fine and luminous. (Common).

11. (23.11) Biancon di Mozurega. This is the name of a white marble quarried in the Euganean Hills near Verona. It is not very different from the preceding specimen either in usage or in colour, only the grain is less bright. (Common).

901. (Suppl.9.1) Marmo Salino dell'Elba. Not long ago, there was found on the Island of Elba the quarry of a white marble that is said to be saline because it has large shiny crystals. It resembles Parian marble in the shape of the crystals, but it is inferior in whiteness and brilliance, in fact it is often marked by greyish bands; nonetheless it is successfully used for sculpture. (Very common).

The term salino or 'saline' was sometimes used in the past when describing 'true' marbles. In 1776, Baldinucci i described 'saligno' as a kind of marble quarried at Carrara which did not freeze, had the lustre of salts and which in damp weather would sweat continuously making it difficult to carve ('…che tiene alquanto di congelazione di pietra, e à in sèque lustri che si veggono nel sale. E' alquanto trasparente; e perchè ne' tempi umidi continuamente suda, con gran fatica s' intaglia in figure.'). This suggests saline marbles had the luster of salt and were, like some salts, hygroscopic, a property not normally associated with this kind of rock. Pinkerton ii wrote in 1811 of marbles that 'present what they call a granular fracture, of a shining or saline appearance', a description which concurs with Corsi's. The term is now obsolete.

Elba is not known for its marble. Two 19th century accounts, however, confirm it was a short-lived source available in Corsi's time. Jervis iii in his 1862 account of the mineral resources of Central Italy comments that '… wherever [magnetic and specular] iron ores are found in any quantity in the Apuan Alps, the Grossetano, or Elba they are invariably accompanied by saccharoidal white marble.' and Hull explains further: 'The quarry was opened by the Emperor Napoleon I when in exile there but after his departure it was neglected.' iv . Napoleon was a great enthusiast for marble and other decorative stones. His exile on Elba lasted from 1814 to 1815.

i. Baldinucci (1681) 140ii. Pinkerton (1811) 380-381

iii. Jervis (1862) 56

iv. Hull (1872) 130

Species II

Palombino marbles (Marmi palombini)

Palombino marble is understood to be that either not adapted or seldom used for statues,[p24] off-whitish in colour, never gleaming white, often tending to light grey or yellowish and in a way similar to the feathers of wood-pigeons for which reason many people still call it 'marmo colombino'. The grain is very fine, the texture compact, and the fracture without lustre. The calcareous substance seems to be combined with a little magnesia, sometimes also alumina, and clay.

Varieties

12. (24.1) Marmo Palombino antico. Marmor Coraliticum. Pliny 26 mentions a marble called 'coralitico', also known as sagario, because it was found on the banks of a river called by some 'Coralio'and by others 'Sagari' 27 that had its sources in Phrygia. He says it resembles 'ivory as much in colour as in texture', and attests that there were 'not any pieces of it measuring more than two cubits'. Whoever sees the marble called Palombino in modern times will be convinced that it corresponds [p25] perfectly to 'marmo coralitico', since it appears to the eye as Pliny described it. That marmo palombino would not have been found in pieces greater than two cubits is well demonstrated by observing the use that the ancients made of it and in those works that happen to be left to us. Palombino was usually used for inlaying internal paving as small, separate, quadrilateral and rhomboidal pieces. In the Galleria de' Candelabri in the Vatican Museum there are two cinerary urns of this marble, not more than a foot in height, one is numbered 1565, and the other 1178, with the inscription 'T. Claudio Successo'. The largest vase I know of, but which does not exceed the measurement of two cubits, is in the possession of Mr Dodwell, to whom I referred in speaking of Parian marble. The Romans also used it for sculpture, for among the busts of the Twelve Caesars in the Palazzo Altemps there are two of palombino. (Very rare).

A cubit is c.one and a half feet, (46 cm); four cubits c. six feet (1, 830 cm).

Gnoli i suggests that the provenance of palombino was uncertain, but that this reference by Corsi to Pliny 'might have serious foundation'. It is a stone that was easy to cut because of its homogeneity and relative softness. Small pieces in a variety of shapes may be seen illustrated in I Marmi Colorati ii , catalogue of an exhibition held in Rome in the winter of 2002-03.

The busts of the Twelve Caesars are still in the loggia of the piano nobile of the Palazzo Altemps, which was sold to the Holy See in 1887, and acquired by the State in 1982 iii .

i. Gnoli (1988) 259-260ii. De Nuccio & Ungaro (2002)

iii. Cresti & Rendina (1998) 174-181

13. (25.2) Another palombino antico of a darker colour, tending [p26] to grey. This variety, it is said, might have come from Egypt, and I do not find it difficult to believe as in the aforesaid Galleria de' Candelabri in the Vatican Museum there is an Egyptian idol of this same marble registered with the no.562. (Rare).

Gnoli i (see 12 above) also says that differing qualities of palombino 'a dolomitic limestone' were used in the Pharonic period, and that it occurs in different localities in the Eastern Egyptian desert.

i. Gnoli (1988) 259-26014. (26.3) Travertino di Tivoli. Marmor Tyburtinum. Marmo Tiburtino, commonly called travertine, is classed with the palombino species. Although it may be said to belong to the palombini in grain and colour, it is however of a different formation, that is by sedimentation. Vitruvius 28 thought it the best stone for construction because when exposed to the air it not only resists inclement weather, but also becomes more resistant. Many monuments in Rome, including the Flavian amphitheatre, justify the assertion of the learned architect. Travertine is generally porous, but in spite of this some very compact pieces are found, and then it can take a good polish. Giorgio Vasari 29 praised highly the quality of travertine used in the two carved salamanders to be seen on the [p27] façade of the church of S. Luigi de' Francesci. (Very common).

Travertino di Tivoli is indeed a travertine, a chemical precipitate deposited from hot springs, and rightfully belongs with his alabastri and tartari (nos. 294-388). Corsi's term 'per sedimento' is a little confusing in that limestones such as the palombini are deposited by a process of sedimentation of calcareous mud, shell fragments etc.

Very large quantities of Travertino di Tivoli have been used in Rome from ancient to modern times. It is relatively soft to cut at first but hardens with time and exposure to the elements, and this, as Corsi says, has made it a very durable building stone. The cavities which are such a characteristic of this stone, are left where plant material and other debris trapped in the travertine during its formation, has decayed away. Today, the holes are generally closed up with an epoxy filler before the stone is polished.

The Flavian Amphitheatre is now better known as the Colosseum. It was used as a 'quarry' for travertine for some 400 years following earthquake damage in the mid-14th century. Claridge i tells the history of this, and of many other buildings and sites.

Vasari ii writes about the salamanders: 'These [carvings of a Frenchman named Maestro Gian, including the salamanders] … bear witness to the excellence and quality of the stone [travertine] which … can be worked as freely as marble. … Michelangelo Buonarroti ennobled this stone in the decoration of the court of the Casa [Palazzo] Farnese. With marvellous judgement he has used it for windows, masks, brackets and many other such fancies … worked as marble is worked.' These comments may account for Corsi's inclusion of travertine among decorative, rather than building, stones. Later iii he classes them among the latter.

i. Claridge (2010) 312-319ii. Vasari 1.12, tr. Maclehose (1960) 52-54

iii. Corsi (1845) 75-76

15. (27.4) Marmo di Segni. The colour tends to be a little greyer than that of palombino antico. It is used for lithography, but with little success because sometimes it is porous. (Common).

16. (27.5) Pietra litografica. Better adapted than the above for lithography, in fact the best of all, is the 'lithographic' stone from Munich in Bavaria. It is of a colour between pea-green and yellowish, and is of a surprising compactness. (Common).

Lithography had been invented by a Bavarian actor and playwright Alois Senefelder i , ii who made a chance discovery that the fine-grained compact Jurassic limestone from Kelsheim could be used as a plate for printing purposes. Joining with a family of music publishers, Senefelder spent the following years perfecting the process as an economic alternative to the use of copper plate. He publicised his findings which were translated into French and English in 1819. Lithographic stone was a comparative novelty among the dealears when Corsi was forming his collection.

Quarries in the southern Franconian Alb were to provide the best quality lithographic limestone for more than a hundred years, until the introduction of new cheaper technologies. The deposit of rock known as 'plattenkalk' extends from Langenaltheim in the west to Kelheim in the east, but the best stone for lithography came from the Solnhofen area. This easily cleaved stone has been used for building purposes since Roman times.

Plattenkalk is also famous for its exceptionally well preserved fossil remains of plants and animals, including the primitive bird Archaeopteryx lithographica.

i. Pennell (1915) 5-29ii. Barthel (1990) 1-16

17. (27.6) Marmo bianco di Fuligno. Palombino background, with some very fine grey veining. (Common).

18. (27.7) Palombino di Mozurega, near Verona. Almost like marmo coralitico. (Not common).

19. (27.8) Palombino di Ancona. A little whiter than the one above. (Not common).

20. (27.9) Bianco di Parma. Palombino background with some tortuous grey veining. (Not common).

21. (27.10) Bianco di Malfesine. Creamy-white background with some rose-coloured markings: from the Euganean Hills. (Not common).

Species III

Yellow marbles (Marmi gialli)

§ I Giallo antico (Giallo antico, Marmor Numidicum)

From Numidia, today the Barbary Coast, a province of Africa and precisely from the sides of the Moorish mountains (monte Maurasido), there used to be extracted a yellow marble which cannot be other than the marble we call 'Giallo antico'. Pliny 30 observes that the revenues of Numidia used to lie in the trading of wild beasts and yellow marble; from this it can be deduced that a very great deal of it would have been quarried. There is an astonishing quantity of it to be seen in Rome, in large masses too, such as the eight superb columns of the Pantheon, those of the Lateran Basilica and of the Arch of Constantine. The shades of colour that are seen in this marble correspond perfectly with those noted by the ancient writers. Sidonius Apollinaris 31 likened it to[p29] ivory and Paulus Silentiarus 32 to gold and saffron. In the various specimens that I shall describe, precisely the above tints can be observed. Martial 33 also called it Libyan marble. Its texture is compact, the grain very fine. Although the yellow marbles, as much the ancient as the Italian, would almost always show some veins of another shade of yellow, either lighter or darker, nonetheless mineralogists consider them as monochrome. See Linné. 34

The Barbary Coast, named after the Berber people, was a term used by Europeans for the North African coast from the Atlantic to the west border of Egypt at the time of the Ottoman Empire. It was associated with the raiding shipping and trading of Christian slaves by the Moors.

Corsi (1845) notes i that since Numidia and Libya are so near one another the same marble was called either Numidian or Libyan. At the end of the 16th century Del Riccio ii states that the marmo giallo was known as Numidico in antiquity, and that the quarry was said to be in Egypt.

It is now known that Giallo antico has been used for yellow marbles from two locations. The first, Chemtou (the ancient Roman city of Simitthus) in Tunisia was the source of all Corsi's specimens. Huge quantities of stone were quarried, and a canal was dug to transport it to the nearby river and thence to the Mediterranean coast, from where it was shipped to Ostia, Rome and onwards to other parts of the Roman empire.

One of the columns from the Arch of Constantine was taken in 1597 and placed in the Lateran Basilica beside the north door, underneath the organ loft. The arch was largely built of recycled marble, much of it coloured.

For a fine study of the architecture of the Pantheon see Wilson Jones Principles of Roman Architecture iii .

Martial's epigram praises a outstandingly brave and beautiful lion with a fine roar in an Italian arena, likening it metaphorically to giallo antico, drawing attention to their common colour, resilience, place of origin, and regal associations iv .

Giallo antico was quarried from around the second century BC to the third century AD, and for a short period again in the 19th century. The name was apparently also given to yellow marbles from Algeria but these were only used near the quarries and not brought to Rome v .

i. Corsi (1845) 90ii. Del Riccio II, ed. Gnoli & Sironi (1996) 90

iii. Wilson Jones (2003)

iv. Martial 8.55 (Bohn (1897) (8.53 in other versions)

v. Price (2007) 90-91

Varieties

22. (29.1) Wan yellow with markings the colour of wood. (Very common).

23. (29.2) Brecciated with waxy yellow, and dark tawny yellow. (Very common).

24. (29.3) Plain yellow of a vivid colour, known as 'giallo dorato'. (Not common).

25. (29.4) Golden yellow of a richer tint. (Not common).

26. (29.5) Plain yellow of a very pale tint tending to white. Pliny says it would have been the most esteemed of yellow marbles. (Rare).

27. (29.6) Very faint yellow, like flowers of straw-colour. (Rare).

28. (30.7) Golden yellow, with purple veins. (Not common).

29. (30.8) Yellowish red, known as 'carnagione'. Perhaps the tint is caused by fire. (Common).

Corsi i later wrote 'There is a type of giallo antico called carnagione, and as it is very beautiful it is held in great esteem when the tint is natural, but sometimes this yellow acquires the name of carnagione (blush pink) when it has suffered the action of fire.'

The stonecutters recognised this, and Corsi may be suggesting they were not above altering the colour themselves. When baked experimentally between about 300°C and 500°C, samples of giallo antico show this effect. The hue (pale pink to red) depends on the iron content of the stone ii . Theophrastus iii had also noticed a similar effect of fire on yellow ochre. The ancient Romans made use of fire for altering the colour of small decorative inlays of giallo antico iv .

i. Corsi (1845) 91ii. M. Mariottini pers. comm.

iii. Theophrastus 54, tr. Caley & Richards (1956) 56

iv. Adembri (2002) 473

30. (30.9) Golden yellow, with fragments of very pale yellow. (Rare).

31. (30.10) Golden yellow, with veins of yellow tending to purplish. (Rare).

32. (30.11) Deep yellow, with purplish fragments. (Rare).

33. (30.12) Another, darker one with purplish veins. (Rare).

34. (30.11) Yellow brecciated with white, found in Hadrian's Villa with a layer of ash-coloured calcareous deposit formed by the water of the river at Tivoli. (Very rare and perhaps unique).

The curious grey coloration is the result of reduction of the iron colouring the marble during prolonged immersion in the river. The sides of the specimen have the typical yellow colouration shown by giallo antico.

§ II Yellow marbles of Italy (Gialli d'Italia)

Varieties

35. (30.1) Giallo schietto di Siena, of a plain, rich colour very similar to the ancient, only less vivid. (Common).

Giallo di Siena is a beautiful egg-yolk yellow and can match giallo antico for its beauty of colour and slight translucency. The finest stone has come from Montarrenti, near the town of Sovicille. Quarrying of the stone has taken place on a relatively small scale for many centuries, but became far more commercial in the 20th century, and it has been exported worldwide. Some quarrying still takes place i .

i. Price (2007) 92-9336. (31.2) Giallo brecciato di Siena. Background of dark yellow, with whitish and waxy grey fragments. (Common).

37. (31.3) Broccatello di Siena. Bright yellow ground with many purplish markings. According to Ferber 35 it is quarried near Montorrenti. The pilasters of this marble in the Church of S. Antonio de' Portoghesi are very beautiful. (Common).

Broccatello was so-called because of its similarity to the richly textured fabric, usually of silk with gold or silver thread, known as brocade. It should not be confused with the Spanish broccatello (nos. 390-393).

Ferber i is discussing 'The cabinet of natural curiosities that had been bequeathed to the University and Academy of Siena by the Professor of Natural History, Dr Guiseppe Baldassari.' ii . Ferber describes broccatello di Siena as 'a yellow marble with black veins; the ground sometimes purple; burning makes the whole red coloured'… dug … eight Italian miles distant from Sienna; generally known and much employed in Italy.'

Like giallo di Siena (nos.35, 36), Broccatello di Siena has been quarried at Montarrenti, near Sovicille and because the land has been owned by the Convent of Montarrenti, it is also known as convent Siena iii .

i. Ferber (1776), tr. Raspe 247, 251ii. MUSNAF (2005-2011)

iii. Price (2007) 92-93

38. (31.4) Marmo scuro di Trento. Very deep yellow that because of the colour, and because of the form of the veins, looks like a wood. (Rare).

39. (31.5) Giallo di Saltrio, in the Milanese area. Ground of light yellow and slightly reddish, with veins of a canary yellow. (Common).

40. (31.6) Giallo di Brianzo, in the Milanese area. Ground of yellow similar to the ancient marble with grey veins. (Common).

41. (31.7) Giallo di Torbe, in the Veronese area, is of a dark and faded hue. (Common).

42. (31.8) Giallo di Verona. Light ground with small, dark veins. (Common).

43. (31.9) Pomorolo di Mizzolle, in the Veronese area. Ground of very light yellow with darker yellow veins [p32] and some purplish markings. (Not common).

44. (32.10) Giallo di Sentro, in the Veronese area. Ground of light yellow with fragments of darker yellow. (Common).

45. (32.11) Giallo, e turchino di Mizzolle, in the Veronese area. Grey ground tending to dark blue with large markings of a golden yellow. A very beautiful marble and (rare).

46. (32.12) Giallo di Lubiara, in the Veronese area, of a single very pale shade of yellow. (Common).

47. (32.13) Giallo di Torri, near Lake Garda. Ground of a strong yellow with paler markings. (Common).

48. (32.14) Giallo di Mizolle in Val Pantena. Ground of canary yellow with many rounded white markings. (Rare).

49. (32.15) Mandolà di S. Ambrogio, in the Euganean Hills, is a mixture of light yellow, with reddish markings. (Common).

50. (32.16) Mandolà di Monte Baldo, near Verona. Blush pink ground with markings of light yellow. (Not common).

902. (Suppl.9.1) Giallo venato di Siena. Light yellow ground marked by a darker yellow, and lined with dark purple. (Common).

Species IV

Blush pink marbles (Marmi carnagione)

Many pure lithologists, as well as mineralogists, assign a marble they call blush pink to a separate species, since, although it is monochrome, it presents in different samples the various shades of skin tone. Linne 36 calls it 'marmor Cinnamomeum'; and Ferber 37 refers to it as 'Cannella', and he puts it among the ancient marbles. However I believe that he might have been mistaken, both because I have never found it used in ancient sculpture, and because I myself have gathered pebbles of it in streams flowing from the Apennines, where I must believe that the mines might be. This marble is delicately coloured very beautiful in appearance, very compact, and of a very fine grain.

Carnagione literally means complexion. This is not a term used in English for colour, and in my [LC] opinion the nearest equivalent is 'blush pink'. Carnagioni are classified as 'Italian' (i.e. modern rather than ancient) although Corsi says that nos. 55 and 56 were 'thought to be ancient'. In Delle pietre antiche (1845) i he omits carnegioni altogether. However, no.60 may have been used for flooring in Pompeii ii .

Pink limestones like this were indeed quarried from various locations in Umbria and Marches regions of the Apennines. The stone from Monte Subasia, known as pietra rosa di Assisi was used for the Basilica of St Clare and other buildings in that city. Corsi's Cottanello marble (no.187) is another example of his marmi carnagione, but brecciated as a result of movement of the rocks along a major fault line that runs through central Italy iii .

i. Corsi (1845)ii. L. Lazzarini pers.comm.

iii. Price (2007) 112

Varieties

51. (33.1) Rosetta di Bergamo, almost white, with a hint of rose colour. (Rare).

52. (33.2) Carnagione d'Asti. Similar in colour to a pale rose. (Not common).

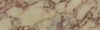

53. (34.3) Persighina di Mosurega. Similar to a pale peach blossom. It is found in the Euganean Hills. (Not common).

54. (34.4) Carnagione di Terni. A little lighter than the above mentioned. (Not common).

55. (34.5) Marmo cannellino chiaro. Pale cinnamon colour. This is thought to be ancient. (Rare).

56. (34.6) Marmo cannellino scuro. Dark cinnamon colour. This is also thought to be ancient. (Rare).

57. (34.7) Palombino rosso di Ancona. Commonly it is called palombino, but it belongs to the blush pink marbles. (Very rare).

58. (34.8) Carnagione di Perugia. Of a cinnamon colour tending to wood colour. (Rare).

59. (34.9) Rossino degli Appennini. Of a blush pink colour tending to purplish. (Not common).

60. (34.10) Carnagione di Camerino. Almost verging on red. (Not common).

Species V

Red marbles (Marmi rossi)

Varieties

61. (35.1) Marmo rosso antico. Marmor Alabandicum. It is truly an extraordinary thing that the quarry and the ancient name of such a beautiful, rare, and altogether so well recognised a marble as rosso antico should not be known. Some writers, in order to attempt to say something, have supposed that the red might have been a marking of giallo antico, but I do not believe this view is well founded. Indeed, if there had been this supposed union of colours between the red and the yellow it would be apparent in large or small markings. Consequently there would have been some examples of red marked with yellow, and some of yellow marked with red, but it has never been seen among the many red and many yellow marbles that are in Rome. [p36] Perhaps one might be tempted to think that the so-called 'rosso brecciato' which without doubt corresponds to the Lydian marble as will be seen at the proper time, might be the same as rosso antico but the differences of colour and of texture exclude this hypothesis.

Rather than be silent with the other writers, I venture to say that rosso antico corresponds to marmo Alabandico. Pliny 38 in referring to this marble, says that it used to be quarried in Asia Minor, near the city of Alabanda from which it takes its name, and he describes it as 'black, that in appearance inclines a great deal to purple'. From this it is understood that Alabandico was not absolutely black, because it was toned with purple, nor was it purple colour, because it was mixed with, and originated from, black. Anyone who looks carefully at rosso antico will see that it does not present a vivid red, but an extremely deep red similar to the colour of animal liver. A black that tends in the least to purple could do no less than appear as a liver-coloured red. Neither should it be said that ancient purple [p37] might have been of violet colour because the very accurate writer, Cornelius Nipotis 39 , in speaking of purple, explains it thus, 'When I was a young man the violet purple used to be held in esteem, but soon after that the Tarantine purple-red was more highly regarded.'

If in the youth of Cornelius, which was in the time of the Republic, the purple-red was already in use we must conclude that it would have remained in use until the time in which Pliny was writing. From this it may be inferred that the colour of marmo Alabandico was of a black, tending to red, and could correspond very well to that known as 'rosso antico'. This marble has a very fine grain, the dark colour is often marked with a bluish-grey white, and almost always shows long, thick curved lines in reticulate form. The famous fauns of the Vatican and Capitoline museums are of such marble. The largest masses of this marble are the fourteen steps that lead up to the high altar in the church of S. Prassede and the two extraordinary columns eighteen spans high in the Camera dell'Aurora of the Palazzo Rospigliosi. [p38] Meanwhile, as I write, there have arrived in Rome two beautiful columns, thirteen spans high, now to be seen in the studio of the sculptor Sig. Pozzi in via del Corso near the church of S. Giacomo degl' Incurabili. (Very rare).

When Corsi wrote his second edition of Delle pietre antiche in 1833, he admitted making a mistake in correlating rosso antico with Pliny’s stone from Alabanda purely on the criteria of colour, without considering other physical properties i . He explains that Pliny’s stone could be melted by fire, which he says indicates a quartz or feldspar base. Rosso antico, being composed of calcium carbonate, would form lime when heated, and would not liquefy.

Pliny makes no mention of a marble from Alabanda. His description is of ‘carbunculus’ which, according to Bostock’s translation ii , has proof against the action of fire. Even in Corsi’s time, mineralogists understood this stone to be garnet, and more specifically the iron aluminium garnet known as almandine, named after Alabanda where, Pliny tells us, it was cut.

Rosso antico was one of the coloured stones most admired by the ancient Romans, because of the association of ideas with 'imperial purple' iii , iv . Ferber v describes it as 'dark red; scarce and dear'. Propertius vi , in a song to his love suggests that the art of song is more attractive to her than material luxuries, such as pillars of Taenarian marble, ceilings coffered with ivory set in the midst of gilded beams, orchards as fine as those of Phaeacian king, Alcinous vii or elaborate artificial grottoes watered by the Aqua Marcia, which was renowned for its cold, clear drinking water viii . Gnoli ix suggests that the marble from Tenaros, mentioned by Tibullus and Propertius and cited by Corsi (see no.71), is rosso antico, and not nero antico, a view that is now generally held.

Corsi refers to a number of places where rosso antico can be seen in Rome. Both the fauns that he mentions were found at Hadrian's Villa. In the medieval church of S. Prassede the wide rosso antico steps lead up to the choir. The large columns mentioned by Corsi are at the entrance to the Camera dell'Aurora where Guido Reni's ceiling fresco of Apollo and Aurora was very greatly admired, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is in the private art gallery known as the Casino of Aurora x .

i. Corsi (1833) 93ii. Pliny 37.25 tr. Bostock (1855)

iii. Deér (1959) 144

iv. Gnoli (1988) 187-191

v. Ferber (1776) 218

vi. Propertius 3.2.11-14, ed. Camps (1966) 61

vii. Homer 7.110-135, tr. Murray (1919)

viii. Schram (2004-2011)

ix. Gnoli (1988) 89, note 5

x. Benzi et al. (1997) 176-79

62. (38.2) Another rosso antico, less dark and (even rarer).

63. (38.3) Porporina della Villa Adriana. This stone resembles imitation purpurin, and it is to be found in the excavations of Hadrian's Villa, near Tivoli. It is porous, but of a beautiful colour. (Very rare).

Purpurin, a reddish purple dye, was extracted from the root of the madder plant. It was not until the 19th century that it was prepared artificially. It was also the name given to a red glass that was sometimes used as a frame for examples of micromosaic designs.

Corsi uses the present tense 'si trova' indicating that at the time of writing it had been found recently. This stone seems to be particularly rare in collections of ancient marbles. A specimen in the Borromeo Collection i '198 - Rosso antico porfidino e porporino della Villa Adriana. Rarissima.' is probably the same stone.

i. De Michelle & Zezza ed. (1979) 8564. (38.4) Rosso di Sabina. The colour is dark, dull, base, and takes a mediocre polish. (Very common).

65. (38.5) Rosso di Newhaven in England. This is the most beautiful red marble known, because its colour is similar to scarlet. It is difficult to find pieces larger than the sample here. (Very rare).

This is one of several specimens of Derbyshire stone given to Corsi by the William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire. Most are more highly polished than other samples in Corsi's collection, strongly suggesting they were cut in England to the dimensions that Corsi required, before being sent to Rome.

Corsi's block appears to be one of the earliest provenanced samples of Duke's red marble. A small amount had been found during excavations in 1819 for a new coaching inn on the toll road at Newhaven, Derbyshire i . The Duke's account books in the archives at Chatsworth record that a shaft was sunk in Newhaven for the new red marble ii , iii , and this was most probably the source of Corsi's specimen. As reserves were depleted, the 7th Duke (1808-1891) had all remaining Duke's red taken from the ground and stored at Chatsworth House to be used very sparingly. Apparently in the past the stone was watered every day to keep it in good condition.

Various authors reported that' Duke's red marble' had been found in 1830 at Alport near Youlgrave, 7km to the north-east. However, Thomas and Cooper, in their paper 'The Geology of Chatsworth House, Derbyshire' iv , say this material, which was also used for inlay in decorative table tops, was a solidified iron-rich sediment derived from mine drainage channels in the Alport area.

i. Farey (1811) 403ii. Chats. Acc., m. (1823)

iii. Brighton (1995)

iv. Thomas & Cooper (2008) 30

66. (38.6) Rosso di Seravezza. Colour tending to deep purplish. (Very rare).

67. (39.7) Rosso di Prodo, near Orvieto; somewhat similar to the ancient, but less vivid. (Common).

68. (39.8) Rosso di Taormina, in Sicily. A little lighter than the ancient, tending towards blush pink. (Very rare).

69. (39.9) Rosso d'Abruzzo. Of a colour between that of the ancient marble, and that of the English one. (Rare).

70. (39.10) Rosso di Lugo. Ground of a pallid red, with markings of a darker red. (Common).

903. (Suppl.10.1) Rosso antico. Ground of a very beautiful red verging on purplish, with markings of bluish-grey white, and others of a bright red verging on scarlet. Very beautiful and of (extraordinary rarity).

Species VI

Black marbles (Marmi neri)

Varieties

71. (39.1) Marmo nero antico. Marmor Taenarium. A black marble that Pausanias 40 called Taenarian (Tenario) used to be extracted from the Taenarian promontory in Laconia. At the end of the best times of Roman rule it was held in very great esteem and the poets Tibullus 41 and Propertius 42 referred to it by indicating a marble of the greatest sumptuousness. [p40] The grain is fine, the texture compact, and the colour is of deep black. Sometimes, however, it shows a white capillary line, short, straight, and broken. Beautiful examples of this marble can be seen in the Capitoline Museum, but the largest piece known is a superb table in the Palazzo Altemps. (Very rare).

Pausanius does not mention marble or a quarry in connection with the promontory of Taenarum only a temple like a cave, with a statue of Poseidon in front of it i . The best times of Roman rule referred to by Corsi were, according to Edward Gibbon ii (who voiced the scholarly opinions of the time), the Late Republic; that is, until the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180AD, and that the mores, or lifestyle and morals, of the Empire led to its decline and fall.

When Corsi wrote about nero antico in 1845 iii , he uses the less positive subjunctive mood (il congiuntivo) suggesting he was not sure of the correspondence between nero antico and Taenarian marble. 'Reasonably therefore it could be said that the Taenarian marble (marmor tenario) might correspond (corrisponda) with that said to be nero antico.'

It turns out that he was correct; black limestone (nero antico) was quarried on the Mani peninsular in antiquity iv but probably not in large quantities. Gnoli v however, thinks that the two poets Tibullus and Propertius could only have been alluding to rosso antico (see no. 61), a view that is now generally held.

Nero antico was obtained from other locations too. Pliny vi says that in the neighbourhood of Munda in Spain there is black stone like that of Taenarium, which had come to be esteemed as much as any marble. This sample of Corsi's may well be from Gebel Aziza in Tunisia.

The Palazzo Altemps was begun in 1480, but had a chequered and somewhat sad history, as did the Altemps family, though Cardinal Marco Sittico Altemps bought it back from Cardinal Soderini in 1568, and added more classical statues vii . In Corsi's day it was almost certainly still owned by the family, and contained their collection of sculpture, but it was rented out to tenants who got a name for splendid parties inviting the Roman nobility. In 1982 the building was sold by the Holy See to the Italian State. It was completely restored over 15 years, and is now a museum with sculpture from great Roman collections, including the Ludovisi and the Mattei .

i. Pausanias 3.25, tr. Jones (1926) 159ii. Gibbon (1776), ed. Saunders (1952)

iii. Corsi (1845) 94

iv. Bruno & Pallante (2002)

v. Gnoli (1988) 189, note 5

vi. Pliny 36.29, tr. Bostock & Riley (1855)

vii. Cresti & Rendina (1998) 174-185

72. (40.2) Nero di Ashford. Takes a very beautiful polish, but when seen near nero antico it is the colour of roasted coffee. (Not common).

Nero di Ashford, known in England as Ashford black marble or Derbyshire black marble, has been used since at least 1590 at Hardwick Hall (a house in Derbyshire also built and owned for many generations by the Cavendish family). Production was greatly increased by the introduction in 1748 of the first water-powered marble mill in England at Ashford-in-the-Water. This led to widespread popularity of this bituminous limestone for various decorative objects including etched, engraved, and inlaid work, as well as stands for decorative objects and sculpture, and as architectural elements i .

Corsi's sample would have been one of those sent to him by William Cavendish, the 6th Duke of Devonshire. As with the sample of Duke's red (no. 65), it was most probably cut and polished in the Duke's Derbyshire workshops. However, according to Yarrington ii , the Duke also had quantities of Ashford black marble sent to Rome to be sculpted there into busts, tazze, obelisks, etc. under the supervision of his agent, Gaspare Gabrielli.

Corsi's observation that Ashford black marble polishes to a slightly brown tint of black when compared with nero antico is correct. However, it was preferred as the ground for marble inlay work in both the Derbyshire and the Devon workshops because it is less brittle than Belgian black marble, which was used for this purpose in the Florentine workshops, and is consequently rather easier to work iii .

i. Tomlinson (1996) 12-32ii. Yarrington (2009) 60

iii. M. Halliday pers. comm.

73. (40.3) Pomorolo di Prun, near Verona. Similar to that from Ashford, but with darker veins. (Rare).

74. (40.4) Nero di Torino. Dark ground flowered by a paler black. (Not common).

75. (40.5) Nero di Trapani. A little less dusky-black than nero antico. (Rare).

76. (40.6) Nero di Como. Perhaps the most dusky-black of all, with some markings of a glossier black. (Not common).

Section II

Veined marbles (Marmi venati)

In this section, and under this name are included both the marbles rightly said to be ancient and those from Italy which are neither monochrome nor brecciated, but show veins, waves, and markings of various colours and formations

Species I

Porta Santa (Marmo Porta Santa, Marmor Jasense)

This name was commonly ascribed to the marble because the doorcases of the Holy Door (Porta Santa) of St. Peter's in the Vatican are made of it. The quarry was on the Island of Iasos (Jaso) in the archipelago on the coast of Caria in Asia Minor, so that it is also called marmo Cario by many authors. Its distinctive characteristic, as noted by Paulus Silentiarius 43 , consists 'of a tortuous and irregular veining, sometimes blood red [p42] , and often of a bluish-grey white'. This veining is very apparent in every part of Porta Santa thus there is no doubt that it would correspond to the ancient marble from Iasos.

The tint is generally reddish, not really bright, and of such variety that it presents all shades of colour excepting green, but not excluding white and a definite black. The grain is fine, and the texture is consistently compact. Four large columns of this marble can be seen in the altar of S. Sebastiano and that of the Presentation, in the Vatican Basilica. There are many fountain basins of it including, among others, that in the Agonal Forum. There are also four amazing columns in the church of S. Agnese fuori le mura.

Portasanta is now the more usual spelling for this stone, which was used for the jambs of the Holy Door (Porta Santa), the most northerly of the portico of St Peter's Basilica. The Holy Door is blocked on the inside most years. A ceremony is held on the Christmas Eve before a Jubilee year when the Pope opens the door with a silver hammer. Pilgrims are allowed to enter the door until the following Christmas Eve when, during another ceremony, the Pope pushes the door shut, and it is blocked on the inside again. The last Jubilee year was 2000.

Corsi was wrong in thinking portasanta came from Caria. The description from Paulus Silentiarius i '… and the glittering marble with wavy veins found in the deep gullies of the Iasian peaks, exhibiting slanting streaks of blood-red and livid white' describes a stone now known as rosso cipollino from Iasos (see nos 95-97). William Brindley ii , a marble dealer and importer, rediscovered quarries for the stone now referred to as portasanta (as used in St Peters Basilica) on the eastern Aegean island of Chios more than forty years after Corsi's death. This is a compact fine-grained limestone breccia in shades mainly of red, pink and grey, sometimes with a distinctive reticulated (net-like) appearance.

However some of Corsi's portasanta specimens are not from Chios, for example 85 from Sicily and 86 from France. As these stones have been found in other 19th century collections of ancient marbles labelled 'Porta Santa', it suggests that the name was by no means restricted to Chian marble by the scalpellini of the time.

Corsi's influence lasted well after the discovery of the quarry, for example the catalogue of the Pescetto Collection in the Servizio Geologico d'Italia iii gives the antique provenance of portasanta as Caria.

The Agonal Forum, as it was still often called in the early 19th century, refers to Piazza Navona because it was built over the running track of an athletics stadium for competitive games (agoni) after the Greek style, which was inaugurated by Domitian before AD 86 iv . From the mid-17th century to the mid-19th century, the piazza was flooded a few inches every weekend throughout August, when merrymaking took place among the nobles in their carriages, and the poorer people. Corsi's specific mention of fountains, of which there are three in the piazza, highlights their importance in Rome both in modern and ancient times.

S. Agnese fuori le mura is at the third milestone along the ancient Via Nomentina. It dates from the 7th century and has columns of re-used ancient marble in the nave. The two nearest the altar and two in the centre of each side are of portasanta v . S. Agnese (St Agnes) was martyred in the Stadium of Domitian during his reign and her grave is reputedly in the catacombs below the church.

i. Mango (1972) 85-86ii. Brindley (1887) 47

iii. Corpo reale delle Miniere (1904) 60

iv. Claridge (2010) 234-237

v. Claridge (2010) 439-440

Varieties

77. (42.1) Pinkish-red ground with a few veins of darker red. (Common).

78. (42.2) Dark red ground with white, and blood red, veins. (Common).

79. (43.3) Mixed ground flowered with grey and dark purplish colour. (Not common).

80. (43.4) Bluish green ground with yellowish translucent waves. (Not common).

81. (43.5) Dark red ground with black waves and white veins. (Not common).

82. (43.6) Pale red ground with breccie streaked with grey and peachy colour. (Not common).

83. (43.7) Purplish ground with white markings and yellowish translucent waves. (Rare).

84. (43.8) Dark red ground with white veins and light red breccie. (Not common).

85. (43.9) Tawny coloured ground with black and white waves. (Very rare).

86. (43.10) Purplish ground with breccie of a lighter shade, and small white veins. (Rare).

87. (43.11) Ground the colour of flesh banded with grey, with a large red marking and white veins. (Rare).

88. (43.12) All white, and slightly translucent. (Rare).

904. (Suppl.10.1) Porta Santa reticulata. Grey ground minutely brecciated by a lighter grey and by white with deep yellow markings in reticular form. A beautiful specimen and (rare).

905. (Suppl.10.2) Ligneous red ground with a few grey and whitish markings, and thick irregular reddish lines. (Not common).

906. (Suppl.10.3) Reddish ground mixed with purplish, with white markings and blackish bands. (Rare).

907. (Suppl.11.4) Purplish ground with markings just verging on rose pink and very white bands. (Very rare).

908. (Suppl.11.5) Blush pink ground, with one large stripe of white edged with red. Very beautiful and (vey rare).

909. (Suppl.11.6) Dark grey ground, with purplish markings in the form of breccie, and a band of clear white. (Very rare).

910. (Suppl.11.7) White ground verging on rosy pink with many small red markings (of extraordinary beauty and rarity).

Species II

Cipollino marble (Marmo cipollino, Marmor

Carystium)

On Mount Ochi (monte Oco) near the city of Carystos, there is the quarry of a marble called 'Carystian' (Caristio). It was also known as 'Euboico' by Pollux, since Carystos is on the island of Euboea, today Negroponte. The stonecutters know it under the name of 'Cipollino' for the reason that within the calcareous substance are found long, thick layers of mica which separate readily along the line of these strata similar to an onion. The most common type that Pliny 44 mentioned is 'of a light green, with veins, and waves of a darker green'. Papinius Statius 45 rightly compared it with 'the waves of the sea,' for it resembles them in both colour as well as in form. Seneca 46 observed, however, that marmo Caristio does not always show 'only green, but also other colours', and in fact it is often seen in red combined with white [p45] . The largest columns of this stone, with the exception of the very largest one lying in the courtyard of the Curia Innocenziana, are almost buried in the vicolo della Spada d'Orlando. They belonged to the famous portico dedicated by Agrippa in honour of Neptune, which gave rise to the idea that he would have wished to consecrate to the deity of the sea a marble that showed him the waves. The columns of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina are also remarkable for their size. The grain size is very small, the fracture is striated.

Pliny i mentions Ocha as a city, but Corsi's contemporaries support his assertions that it is a mountain, for example Dodwell ii refers to Okhi Oros as Mt. Oche and adds a footnote 'This mountain is at present called Karystos, and sometimes the mountain of Saint Elias'.

The very large ancient quarries are at Kylindri, above Carystos, on the southern side of the Greek island of Euboea (Evia) and supplied the typical green and white cipollino verde. A great deal of this was used, often as large monolithic blocks and columns, throughout the Roman Empire; so much so that it became rather despised as a symbol of fashionable luxury in Rome. It is sometimes called Carystian green.

The Portico of Agrippa dedicated to Neptune was near the Pantheon iii also first dedicated by Agrippa. It is in the same area of Rome as the Spada Orlando.

The fine Corinthian columns of the Temple of Antoninus Pius and Faustina front the Roman Forum. The church of S. Lorenzo in Miranda was formed of the cella, the inner chamber of the temple, in the 7th or 8th century iv .

Corsi's cipollini come from a number of other locations; indeed cipollino is a somewhat generic name for folded, banded marbles that resemble the layers of an onion (cipolla). Both here and in his Delle pietre antiche, Corsi v describes the different markings and colours that he observes in cipollino marbles, but he does not acknowledge any other provenance. As well as blocks from Tuscany in Italy and Caria in Turkey, he includes samples of cipollino mandolato, the Campan marbles from France which are nodular limestones and would not today be classified with the cipollini. Details are given in the further information for each specimen.

i. Pliny 4.21, tr. Bostock & Riley (1855)ii. Dodwell (1819) v.2, 153

iii. Claridge (2010) 202, fig. 77

iv. Claridge (2010) 111-112

v. Corsi (1845) 98-99

Varieties

89. (45.1) Light greenish ground similar to soap, with a few lateral veins. (Not common).

90. (45.2) Very light green ground with veins of deep green. (Very common).

91. (45.3) Green ground verging on grey with yellowish bands. There are two small slabs of this marble in Rome, in the third chapel to the left in the Church of S. Maria di Monte Santo al Popolo. (Very rare).

[p46]The inlays in S. Maria di Monte Santo are probably more like a stone from the Apuan Alps, and are very similar to some floor slabs in the nave of the Frari in Venice.

92. (46.4) White ground with green waves. (Rare).

93. (46.5) Light green ground with white breccie, known as 'mandolato verde'. (Rare).

94. (46.6) Light red ground with white breccie, called 'mandolato rosso'. My friend Sig. Gaspare Gabrielli, a talented artist and great lover of marbles, owns a very beautiful tazza of this marble. (Very rare).

Gaspare Gabrielli was an Italian landscape artist, who as a young man was brought to Ireland in 1805, by the 2nd Baron Cloncurry, to paint views of Italy in his house, Lyons, where he spent 3 years. Gabrielli taught, established a reputation, and by 1811 was elected vice president of the Society of Artists of Dublin, where he exhibited numerous times. He is said to have painted a room for the 5th Duke of Manchester in Tandragee Castle, and evidently met the 6th Duke of Devonshire, owner of Lismore Castle, who remarked that 'he [Gabrielli] repaired to Rome' in 1814 i ii . Here, according to Yarrington, Gabrielli was 'one of several artists and artisans who specialised in sourcing different varieties of rare marble for sale.' iii He became the Duke's agent in Rome, sourcing and shipping marble sculptures, pedestals, tables etc., to Chatsworth, and corresponding with numerous letters on the progress of the Duke's sculptural commissions and purchases.

When the Duke of Devonshire visited Rome, Gabrielli acted as his cicerone. Together they visited many sculptors' studios, dealers in marble and other objects made of it, as well as museums and sites. It is most likely that Gabrielli would have arranged the Duke's visit to Corsi too. The Duke may well also have heard of Corsi from Lord Compton, who was related by marriage, of the same age, lived in Rome for 10 years, and knew Corsi.

Gnoli iv suggested that cipollino mandolato rosso or Campan rouge was more greatly admired in Rome, because it was rarer than the mandolato verde. Both stones come from France.

i. Cavendish (1845) 60ii. IAA (2012)

iii. Yarrington (2009)

iv. Gnoli (1988) 183

95. (46.7) Ground red all over with a very few white veins. (Rare).

This is the stone variously known as cipollino rosso, marmor Iasense, or marmor Carium from Iasos, Caria in south-west Turkey to which Paul the Silentiary i was referring as Carian (quoted in notes for portasanta). A great deal of it was used in the 'open book' style, decorating Haghia Sophia ('Ayasofya') in Istanbul and San Vitale in Ravenna. There, according to Gnoli ii it is known as 'africanone' or 'africano egizio'.

The stone from Iasos occurs in different varieties. When monochrome red, it is called rosso antico, and can be very difficult to distinguish from the Greek stone of that name iii . It is not in Corsi's collection. Nos 95-97 are typical examples of cipollino rosso; and nos. 389 and 903 are examples of cipollino rosso brecciato; Corsi confusingly calls the latter sample 'rosso antico'. He was understandably confused, and went on to write iv 'there is the red coloured cipollino that is not dissimilar to the antique red marble'.

i. Mango (1972) 86ii. Gnoli (1988) 243

iii. Gorgoni (2002a)

iv. Corsi (1845) 98-99

96. (46.8) Grey ground striped with white and with red veins. (Rare).

97. (46.9) Sample with three distinct patches of white, green, and red. (Rare).

98. (46.10) Ground of an olive green with white waves. (Rare).

99. (46.11) White ground with black waves. (Rare).

100. (46.12) White ground with black streaks. The two columns in the church of S. Maria delle Grazie at the Porta Angelica are of this marble. (Rare).

The church of S. Maria delle Grazie at the Porta Angelica was demolished for road-building after the Second World War.

911. (Suppl.11.1) Deep green ground covered with waves of a pea green. Very beautiful, rare, and perhaps (unique).

912. (Suppl.11.2) Black ground with many dark grey waves. (Very rare).

Species III

Africano marble (Marmo Africano, Marmor

Chium)

[p47]

Although the island of Chios (Scio) in the Archipelago is part of Asia Minor, nonetheless the marble found there is usually, because of a common mistake, called 'Africano', perhaps on account of its dark shades. Theophrastus 47 says that black was the predominating colour, and Pliny 48 adds that it had markings of various colours, characteristics that all fit perfectly with the so-called Africano marble. All the many colours that are seen in this marble are of a surprising vividness, and are distinguished by diverse markings that are neither long like veins, nor concentrated in breccie. The texture is always compact, rather hard to work and not infrequently it contains some veins of quartz. The largest columns of this marble that are known flank the great door of the facade of the Vatican Basilica.

Theophrastus i wrote 'There is also found [in Thebes] a transparent stone, something like the Chian.' From this, the translator Hill concluded that 'Chian was a dark coloured marble, so named from the Island of Chios, where it was dug; something of the kind of the Lapis Obsidianus of Aethiopia, and like it in some degree transparent.' Pliny ii said that in his opinion, 'the first specimens of our favourite marbles with their parti-coloured markings appeared from the quarries of Chios, ... (versicolores istas maculas Chiorum lapicidinae osternderunt).' We now know he was referring to the marble known as portasanta.

Michael Balance iii rediscovered the ancient quarry of africano, in Sigacik (Teos), near Izmir, Turkey in 1966, more than 120 years after Corsi's death. He found fragments of the marble around a curious deep lake which turned out to be the flooded quarry. The Greek island of Chios lies in the east of the Aegean near that part of the Turkish coast (Asia Minor) where Sigacik is situated.